Rumour is, the Fed is letting go of FAIT, so here’s a little bit about it:

Inflation targeting is a straightforward concept: it establishes a nominal anchor for monetary policy, signaling a central bank’s commitment to price stability. New Zealand pioneered this approach in 1990, followed by Canada in 1991, the United Kingdom in 1992, and Sweden and Finland in 1993. These countries adopted inflation targeting either after previous inflation-control measures failed (e.g., Canada and New Zealand) or following the abandonment of policies like pegged exchange rates (e.g., Sweden, the UK, and Finland).

In their paper “Twenty-Five Years of Inflation Targeting in Australia: Are There Better Alternatives for the Next 25 Years?”, McKibbin and Panton argue that strict inflation targeting focuses on achieving and maintaining low, stable inflation—allowing for base drift—without prioritising the stabilisation of output deviations. Under this framework, policy rates are adjusted to accommodate shocks affecting price stability, whether those shocks are temporary or permanent.

According to Frederick S. Mishkin, inflation targeting is a monetary policy strategy that encompasses five main elements:

1) the public announcement of medium-term numerical targets for inflation;

2) an institutional commitment to price stability as the primary goal of monetary policy, to which other goals are subordinated;

3) an information inclusive strategy in which many variables, and not just monetary aggregates or the exchange rate, are used for deciding the setting of policy instruments;

4) increased transparency of the monetary policy strategy through communication with the public and the markets about the plans, objectives, and decisions of the monetary authorities; and

5) increased accountability of the central bank for attaining its inflation objectives.

Comparing Inflation and price-level targeting

This chart from VoxEU illustrates how expectations adjust depending on the monetary regime in place. If the Fed commits to a 2% inflation target and inflation unexpectedly rises to 3% in period 3, the public will anticipate inflation returning to 2% in periods 4 and 5. Conversely, under a price-level targeting regime, the public would expect inflation to fall to 1% by period 5 to correct the deviation. When a shock occurs, the price level rises under inflation targeting and remains elevated. Thus, price-level targeting can produce different outcomes compared to inflation targeting.

The effective lower bound (ELB) is the interest rate below which it becomes profitable for financial institutions to convert central bank reserves into cash. In practice, the lower bound for nominal interest rates is not zero but negative, due to the costs of storing cash. This is why it is termed an “effective” lower bound rather than a “zero” lower bound.

In a scenario without an ELB, a successful discretionary monetary policy would counteract demand and supply shocks while anchoring inflation expectations at the desired target. However, when the ELB is binding, interest rates cannot respond effectively to shocks, resulting in lower inflation and a wider output gap.

Mertens and Williams, in their paper “Monetary Policy Frameworks and the Effective Lower Bound on Interest Rates”, argue that an average inflation targeting (AIT) framework can mitigate the downward bias in inflation. By aiming for above-target inflation when not constrained by the ELB, AIT raises inflation expectations during periods of low inflation. This helps anchor expectations at the target level and reduces the ELB’s adverse effects on the economy.

Unlike conventional inflation targeting, where expectations may become anchored below the target—exacerbating the ELB’s negative impacts—AIT corrects for this downward bias in inflation expectations.

Historical dependence is a crucial element in calculating average inflation targeting (AIT). But what does historical dependence mean? It refers to how far back in time we look to determine the target. Neither the lag in the AIT equation nor the size of the time window used to compute the average has been specified by the Fed.

Powell, at the time, stated that the Fed would not commit to a fixed AIT formula: “In seeking to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time, we are not tying ourselves to a particular mathematical formula that defines the average. Thus, our approach could be viewed as a “flexible” form of average inflation targeting.”

This view was echoed by Clarida: “…nor is it a commitment to conduct monetary policy tethered to any particular formula or rule… At the risk of repeating myself, let me restate it verbatim: ‘…following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.’ Full stop.”

But just for the sake of discussion, what would the AIT formula even look like?

It could look something like this:

For completeness, the inflation targeting rule and the price-level targeting (PLT) rule from “Average Is Good Enough: Average-Inflation Targeting and the ELB” by Amano, Gnocchi, Leduc, and Wagner are included, alongside average inflation targeting (AIT), allowing us to observe and compare their subtle differences.

All three approaches—AIT, inflation targeting, and PLT—aim to raise the inflation rate above the target when monetary policy is unconstrained. Each also relies on shaping private sector expectations, making policy credibility and public understanding critical to their success.

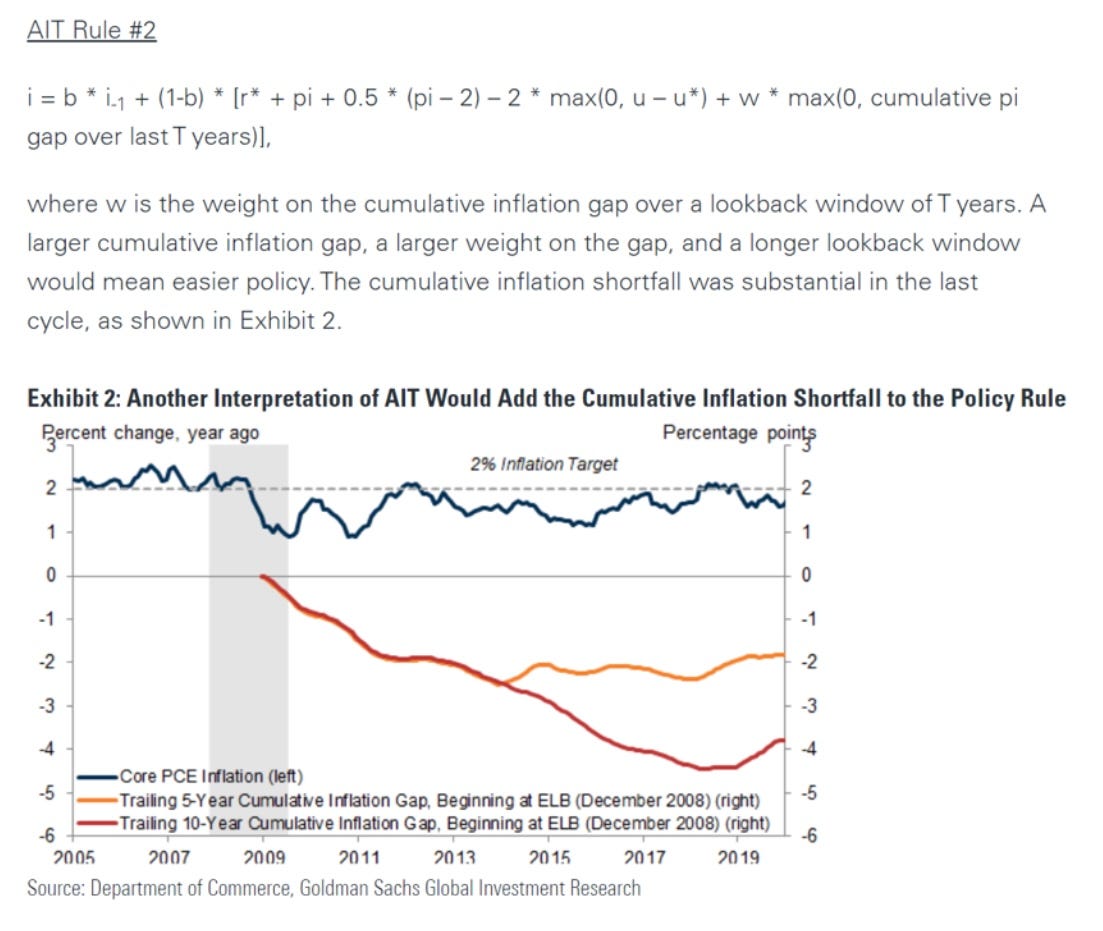

Alternatively, a formula like the one proposed by Reifschneider and Wilcox in their paper “Average Inflation Targeting Would Be a Weak Tool for the Fed to Deal with Recession and Chronic Low Inflation” could be considered. In this work, two former senior Fed economists suggest modifying a “balanced approach” Taylor rule to assign some weight (denoted as w) to the trailing inflation gap.

Policy interest rate = r* + current inflation + 0.5 * (current inflation – 2%) – 2 * (unemployment rate – structural unemployment rate) + w * (trailing inflation gap)

The “lookback window” for the trailing inflation gap varies across different policies. Traditionally, it spans the previous year’s inflation. For price-level targeting, it might encompass the entire inflation gap since the policy’s inception. For average inflation targeting (AIT), however, it could cover the full gap since the effective lower bound (ELB) became binding, or it might use an intermediate window, such as 5 years. The weight (w) applied to the gap could align with the year-on-year gap weight used in conventional policy, typically 0.5.

Goldman Sachs proposes two alternative AIT formulas. In the first, the policy rule temporarily raises the inflation target when inflation has consistently fallen below 2%. In the second, the rule incorporates the cumulative inflation shortfall—possibly since the onset of a recession—as an additional term.

It’s evident from these formulas that, regardless of its specific form, the lookback period is a critical component of AIT.

The “flexible” in “flexible AIT” indicates that AIT is implemented alongside considerations of unemployment, output, and broader domestic and global conditions. Powell emphasised this: “In seeking to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time, we are not tying ourselves to a particular mathematical formula that defines the average. Thus, our approach could be viewed as a flexible form of average inflation targeting. Our decisions about appropriate monetary policy will continue to reflect a broad array of considerations and will not be dictated by any formula. Of course, if excessive inflationary pressures were to build or inflation expectations were to rise above levels consistent with our goal, we would not hesitate to act.” In essence, the ultimate decision remains more subjective than objective.

However, the AIT framework has its drawbacks. Lags between policy implementation and inflation outcomes, combined with vague parameters, weaken the Fed’s accountability. If applied rigidly, AIT risks amplifying large economic shocks when maintaining the average conflicts with the economy’s immediate needs. It also raises questions about its impact on exchange rates.

Reifschneider and Wilcox, in their previously mentioned paper, critique AIT’s effectiveness, arguing that it may struggle to deliver the substantial inflation overshoot required to achieve a 2% average target. At the other extreme, when the ELB is binding, AIT has limited ability to shape expectations, rendering it ineffective in combating recessions or stimulating the economy.

Moreover, AIT cannot significantly narrow the unemployment gap during severe recessions. Reifschneider and Wilcox find that none of the AIT rules they tested substantially improve simulated labour market conditions or curb disinflationary pressures in the first five years following a recession’s onset.

The policy’s credibility hinges on the AIT model’s efficacy and how well the Fed communicates its framework to the public. Currently, public understanding remains hazy—not only because certain elements, such as the specific (non-formulaic) model, its parameters, and the additional criteria defining its “flexibility,” are undisclosed, but also due to the Fed’s unclear explanations.

Perhaps the Fed should recognise that the public can handle uncertainty, provided they understand what they are meant to be uncertain about.