The Fed is reluctant to cut rates over concerns that inflation expectations might harden at a level above 2%. Why is there this reluctance?

Well then, I guess the time has come in this substack for us to talk about inflation expectations in depth, henceforth shortened to “IE” so that I don’t have to rewrite that phrase a thousand times.

Inflation Expectations and The Measurements

What is IE? Simply put, it is what groups of people such as business people, consumers, company managers, financial market participants, etc. expect the future inflation to be.

Although IE is unobservable, there are two main ways we can estimate it:

The first way is via market-based measures. Looking at what the market participants are willing to pay for securities indexed to inflation can give us a clue about where they think inflation is going to go. They can be calculated based on a comparison of derivatives, e.g. inflation-linked swaps.

The second way is through survey-based measures. Here, questionnaires can be filled by various groups to gauge price expectations of goods and services. The survey-based measures contain information about the uncertainty of the future economic outlook. Additionally, forecasts based on business IE are found to be good for one year.

However, the Fed note by Diercks and Munir noted that divergent signals can arise out of these two measures. They found that during the previous 15 years, predictions based on market quotes tend to provide better forecasts of the rates. Market-based measures are probably more accurate than the survey-based measures because of the financial incentive for participants to forecast as accurately as possible.

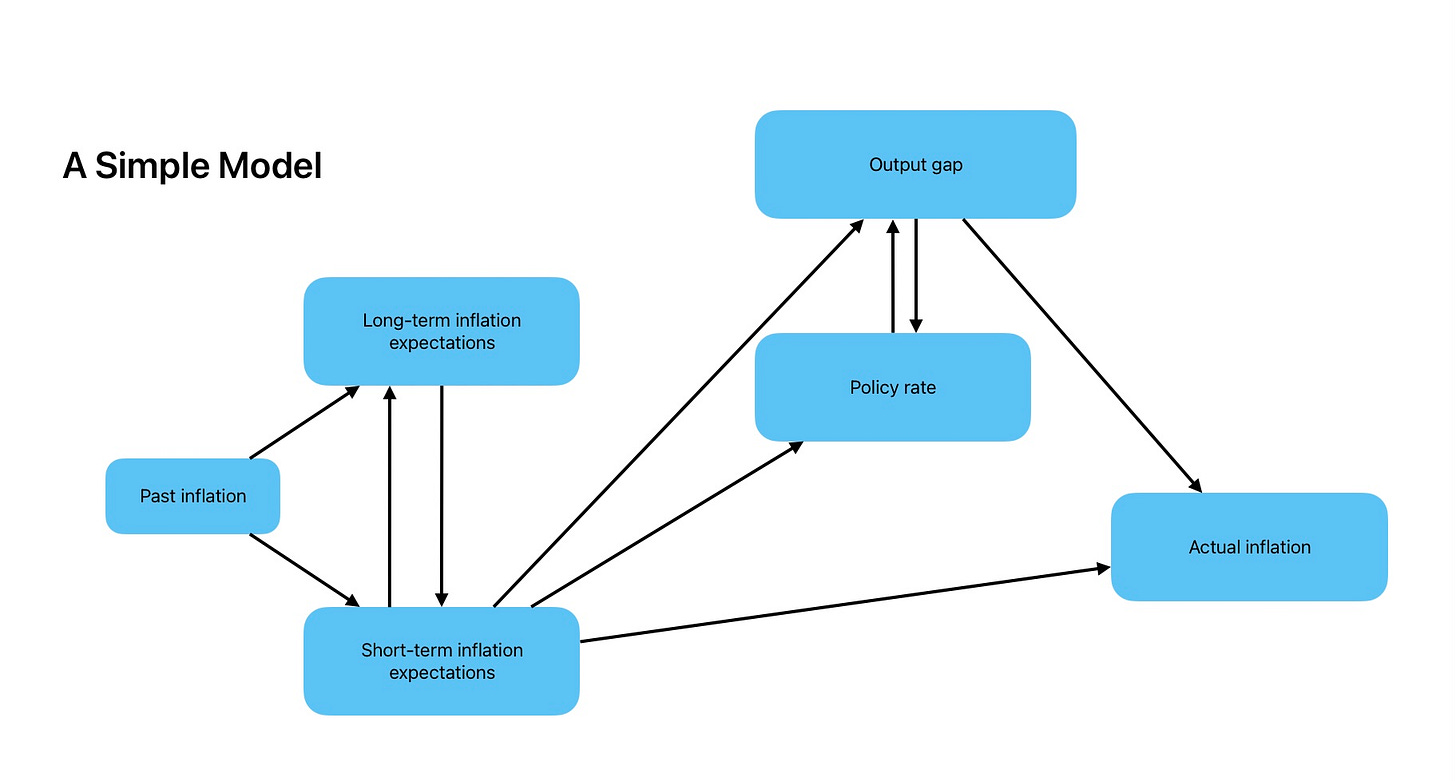

The Formation of Inflation Expectations

Perhaps one of the better models of the formation of IE is the “Full Information, Rational Expectations” (FIRE) model. The model has a few assumptions, the two main ones being that market participants take in the full set of information that encompasses all variables in the model including the variables entire history; and that participants forecast future variables optimally given the full information, i.e. their expectations stay true systematically or predictably to the equilibrium predictions of the model (rationality test).

In reality, studies find that households’ IE departs from FIRE and are heterogenous. They depend on past experience (adaptive expectations) and respond to professional forecasts. Having said that, rationality tests could contain short sample problems and IE appearing non-rational could in fact, in the absence of perfect information, be rationally formed. Diagnostic expectations on the other hand, is where groups form their expectations based on representative heuristics. That is, believing more in a particular future outcome when there is news today to support that belief.

The formation aside, only 10-20% fluctuations in realised inflation have flowed through to IE every year (e.g. two years of 3% inflation (1pp above target) would raise IE by about 20-40bp). Long-run IE changes with time and is loosely connected to the real economy. The strength of this connection also varies over time depending on the running of the monetary policy, past and present, as well as economic growth.

IE also has asymmetric sensitivity. It is more sensitive during periods of high inflation than during low inflation. It is more sensitive to unusually large deviation from 2% rather than small deviation and an inflation overshoot can raise IE in the next cycle. The Fed’s “Common Inflation Expectations Index” model assumes IE are mean reverting. Is this a good assumption?

In the other direction, empirical evidence shows that the long-run actual inflation closely follows the long-run IE and not the short-run IE. In other words, even though it’s hard to see what the rates would be in the short-run, it’s relatively easier to forecast what it would be in the long-run. IE can also be self-fulfilling by affecting supply and demand, which then creates inflationary pressure.

In real life, IE does not respond immediately to monetary policy shocks and when it does, the response is usually small at first, then builds up over time, then declines again. In addition, forecast errors of IE are actually predictable because they depend on the revisions of the previous forecast.

Our most recent experience shows that in the absence of full information, market participants are quite responsive to the Fed’s communication and will adjust IE accordingly. Complimentarily, this episode of high inflation has also taught market participants that the Fed will actively and strongly react to high inflation. With every Fed action, market participants improve their learning of the Fed’s reaction function and this also contributes to the formation of IE.

The Anchoring of Inflation Expectations

From Ricardo Reis (2021), “Inflation has an anchor in people’s expectations of what its long-run value will be. If expectations persistently change, then the anchor is adrift; if they differ from the central bank’s target, the anchor is lost”. Anchoring IE means adopting a credible commitment to an inflation target (e.g. 2%) for the medium to long term; but why is anchoring so important? Being able to anchor long-term expectations means that the Fed is freer to pursue its double mandates of price stabilisation and maximum employment.

We hear the phrase “IE becoming unanchored” a lot, but what does it mean for IE to become unanchored? One of the ways this can happen is when there is persistently larger aggregate demand than aggregate supply. A one-time shock can lead to extreme prices increase, which increases growth rates of prices and wages, which then leads to everyone thinking that the new rates are “normal”. Alternatively, if a post-pandemic high inflation lingers a bit longer than expected but that lingering does not significantly change the long-run expectations, then IE is properly anchored.

An explanation of unanchoring that I kind of like comes from Carvalho, Eusepi, Moench and Preston (2022), which is, “expectations are unanchored when agents doubt a constant long-run inflation mean and switch to a constant-gain algorithm. Expectations display high sensitivity to forecast errors.” (Constant-gain forecasting model means that market participants are highly sensitive to new information and changes their expectation of the long-run mean inflation rate according to the new information).

Inflation Expectations and Inflation Persistence

Inflation persistence happens when the inflation dynamics switch to a persistently high inflation regime. (As an aside, one way to determine this is by using a Markov-switching model of inflation dynamics that can show when there is a regime shift, e.g. higher mean level of inflation and greater inflation uncertainty.)

Shiu-Sheng Chen (2023) shows that IE from the Michigan Survey of Consumers can reliably predict the probability of high inflation persistence. They also find that an increase in IE produces a higher probability of a regime with highly persistent inflation. Referring back to the beginning of this post, this finding means it is even more imperative that credible monetary policy prevents the unanchoring of IE which can lead to persistent inflation above the 2%.

The opposite of “persistent” is “transitory”. The technical meaning of “transitory”, debated intensely on Twitter these past years, does not mean that the inflation shock would be short-lived. “Transitory” means that changes incurred due to the shocks are mean reverting (this also means that we can end up with a higher price level). If the shocks can dislodge a variable, e.g. mean, variance or autocorrelation structure over time, then the shock-induced changes are termed as “persistent”. If the changes are persistent, then we will end up with a different regime, e.g. more volatile CPI, etc.

According to Hooper, Mishkin and Sufi (2019), the economy can move from a stationary regime to a non-stationary regime in the blink of an eye. Stationary inflation shocks have “transitory” effects whereas non-stationary shocks to inflation are “persistent”, leading to unanchored IE.

The word “transitory” is not new in the Fed’s vocabulary, it was even used pre-Covid by Yellen in 2016 in the phrase “asymmetric transitory effects”. In the words of David Andolfatto, “transitory might take a long time.” “Transitory” therefore, is not at all about how long it took for high inflation to resolve but rather, do we end up with a new regime at the end of this? In addition, the test of “transitory” does not depend on what actually caused the high inflation, be it supply-side or demand-side, or a combination of both, but rather, whether the long term IE remains anchored or not.

The ability to tell whether the inflation is going to be “persistent” or “transitory” can massively help the Fed in timing policy and deciding how aggressive the policy should be (anti-attenuation). The Fed can then choose whether or not to look through any transitory overshoot of inflation in favour of long term growth. Normally, the Fed would tighten if they consider risks to price stability or financial stability are increasing. In the 2021 cycle however, the Fed focused on maximum employment, postponing the hikes as long as possible to give a chance for the labour market to recover as broadly as possible. That decision was not without risks and the Fed has since been accused by some of being “behind the curve”.

The Policymaker’s Management of Inflation Expectations

For the Fed, an anchored IE is a testimony to its credibility. From Bonomo et al. (2024), a reduction in monetary policy’s commitment to the inflation target can cause the immediate unanchoring of IE. An example would be when the Banco Central do Brasil abruptly pivoted in 2011, changing their policy from tightening to easing within the span of a meeting. One can imagine how this must have come as a huge shock to the market participants, incurring a loss of faith in the central bank’s commitment. This then, argues for gradualism.

“Gradualism”, as per Brainard’s (not that Brainard, another Brainard) principle (1967), makes a case for the gradual adjustment of policy stance. Since economic data, models and parameters can prove to be uncertain, prudence may be required in policymaking as opposed to when we have greater certainty.

The thinking goes that firstly, a state contingency-based policy stance justifies “gradualism” when it’s less certain where the state is heading to. When there are inflationary components that require further firming in its decline for there to be more certainty, gradualism is key to making the right call at the right time. Secondly, consistency and credibility are greatly intertwined. Aside from the dangers of entrenching a higher rate above the 2%, a Fed that cuts rates and is then forced to abruptly pivot loses credibility for future actions. Short of completely unforeseen economic shocks, a self-proclaimed data dependent policymaker should conduct measured changes in its normalisation phase. Thirdly, taking into account the lags inherent in the process of policy calibration, the whole exercise is iterative and interactive in nature where eventually, the strength of the policy transmission mechanism is discovered. This discovery process requires gradual adjustments.

So, assuming no new shocks from here on for a while, when would be a good time to cut rates?Perhaps in the future, tools such as Generative AI or by using synthetic data would help assist us in answering this question. In the meantime, the Fed has to decide based on the technology today and whatever data is available. But how should it go about deciding?

To weigh the decision, the Fed could look at the strength of inflation persistence and track the evolution of IE over time (trend). Despite the expectation of inflation rates to continue to fall, there are still some odds left that it settles at a rate above the Fed’s 2%, at least for the short to medium term. Are we happy to take the risk of cutting too early?

There could be an argument for the Fed to begin cutting rates because the rectification of being wrong is easy - just hike the rates back up if it proved too early. But do we know whether a second round of hiking right after would give the same constraints?

Preemptively cutting rates is called, in the economics lingo, as “insurance cuts”. “Insurance cuts” in response to a growth scare are not imminent or applicable in our case today, but “normalisation cuts” in response to a sufficient decline in inflation would be a good reason to cut rates. Not cutting rates in time when there is high confidence of normalisation might mean undoing all of the good things we’ve seen happening in wages.

Fed economists John Williams and David Reifschneider came up with some insurance policy rules that instil an asymmetric modification to the Taylor rule. Here, policymakers would aggressively ease when the implied policy rate in the standard rule falls below a particular threshold due to slack or inflation. This has the result of the economy running comparatively hotter than it would have been following a bog-standard Taylor.

In general though, the risk of recession does not lessen with such insurance rules. Easing aggressively due to the fear of recession, which could even be a false alarm, could result in too little room to ease if the real recession comes along. In addition, insurance policy rules increase distortions in financial conditions, leading to overvalued assets and securities.

Waller in his speech, “What’s The Rush?”, said the data shows that we can afford to wait a few months to be sure, whereas as I understand it, Paul Krugman is urging us to do the opposite. As of right now, it’s hard to tell who’s right. Even after the fact, it may still be difficult to determine who was right.

Bonus Section: The Unanchoring of Inflation Expectations

Here is a chart from Reis (2021) that I find interesting.

Martin was the Fed chair during the studied period. Inflation was stable before 1965, confined to a narrow range of 1-2%. This shows that IE was firmly anchored. Post the Treasury-Fed Accord (1951), inflation control was the focus of the day via an independent Fed. However, from 1965 until 1975, IE started drifting and eventually became unanchored, resulting in high and volatile inflation. It was only after the 1980s recession that inflation became low and stable again.

From 1961 until 1965, the US economy expanded with a significant fall in unemployment but without the penalty of high inflation. Half-way through 1965 unfortunately, inflation started rising above 2% and the Fed responded by hiking and tightening financial conditions.

At the end of 1966, monetary policy had reversed and eased again as the Fed believed that it should be in sync with the government who at the time was trying to mitigate the consequences of the Vietnam war. By this time, inflation was above 3% and by the end of the first quarter of 1967, the Fed started cutting interest rates as an insurance against recession. This then, spurred the strong economic growth in 1968 when inflation went above 4.5% to end up at around 6%. The Fed then tightened but this action might have come a little too late.

In early 1970, Burns became the new chair, replacing Martin. Interesting to note that at this time, IE was just a fluffy concept. No one had thought of how to measure IE yet short of tracking the past actual inflation. When Burns took the helm, the US was in the midst of an expansion but still, financial conditions were kept easy. It was at this time that the IE anchor showed signs of drifting. Two occasions, the end of Bretton Woods and Nixon’s wage and price freeze (cheered on by Burns) helped in slowing this down.

Inflation accelerated from 1972 to 1974 (annual inflation rate averaging 10.5%), mainly due to the shocks in food and oil price. Other shocks on the supply side also promoted the acceleration. The resolution of the supply side issues though, did not see a full reversal of inflation. In 1974, policymakers tried to lower IE with a campaign slogan of “Whip Inflation Now”, which didn’t quite succeed as the rally cry was not followed by actions from the Fed. By 1975, the unanchoring of IE was in full swing as the annual inflation rate moderated to 5-7% in the following years.

The Fed communication and actions at the time, gave no indication that it was determined to control inflation to a more reasonable level. Along with the effort of money-supply targeting being seen as unserious, the Fed began to lose its credibility. This loss of credibility weakened the Fed’s policymaking ability and highlighted even more so the importance of being able to measure IE and keeping IE under control.