Let’s Revise

On lags and stronger-than-expected growth

Often times in life we need to revise our measure of a situation. The pandemic was an extraordinary, unprecedented event for which in the recent financial history, we have no comparison for. It is no surprise then that throughout the post-Covid period, time and time again, market participants have found that their various premises no longer apply.

One of the surprises is the strength of the US economy. An expectation of a recession permeated the consensus from the very beginning of the Fed’s hiking cycle and persisted well beyond the evidence of tight labour markets and growth forecasts. The thinking in the early days was that the Fed will hike, constricting the above capacity growth but pretty soon after would be forced to pivot. Lo and behold, the US economy just kept surprising us on the upside, the latest being that the US Q3 GDP grew at 4.9% annual rate, above the consensus forecast of 4.3%.

Overheating in the economy

The Fed raises rates to prevent the economy from operating well above its capacity (overheating) in order to avoid price instability. However, how do we know if the economy is going to overheat?

To answer this, we have to look at both the economic growth (the intermediate target of Fed policy) and inflation (one of the final targets of Fed policy).

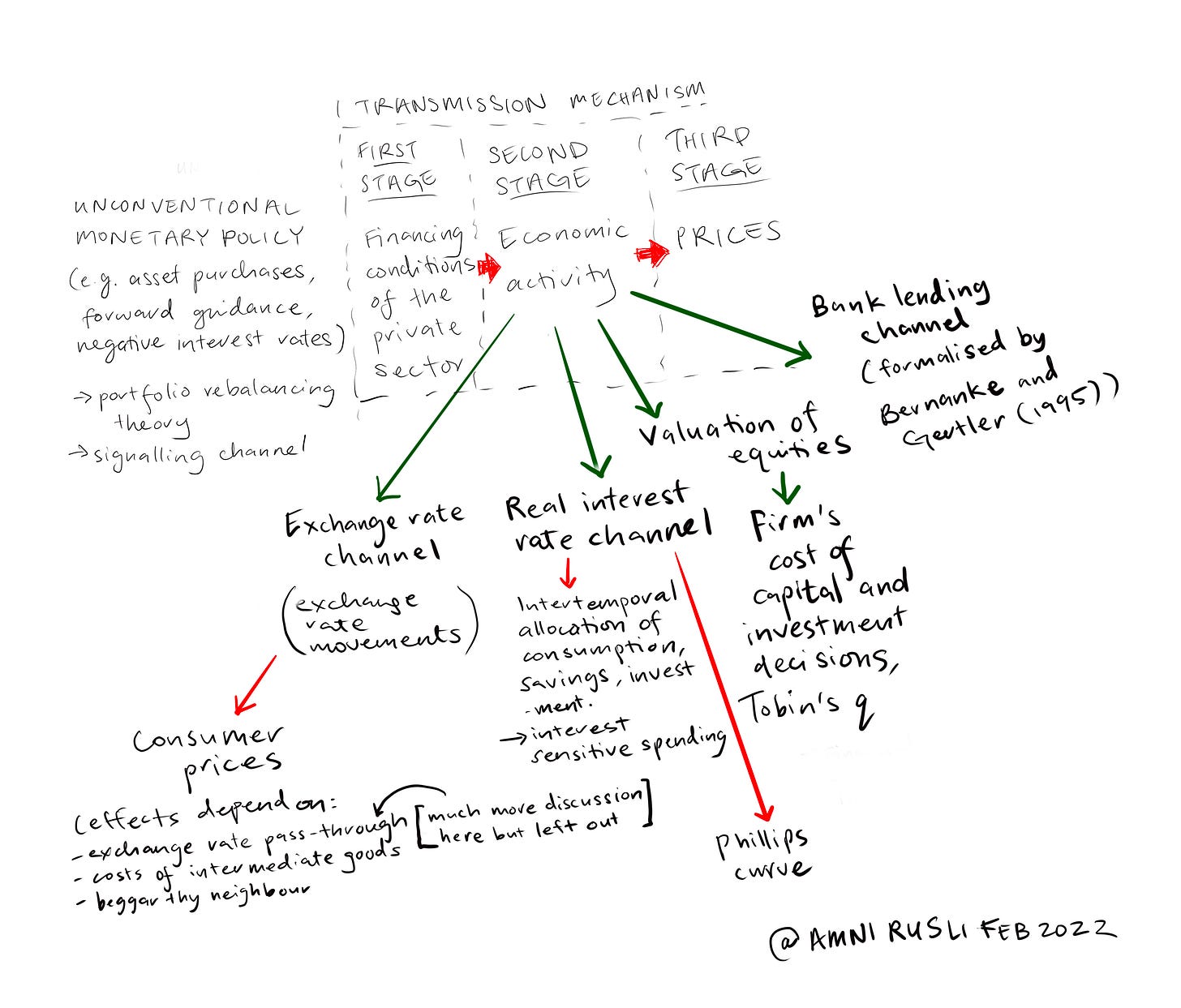

Diagram of the monetary policy transmission mechanism

What are the inflation-inducing factors? Firstly, there were the supply-chain disruptions. Secondly, the demand surge after reopening and thirdly, the potential pass-through from the higher realised inflation to inflation expectations. It is the third one that gives central bankers nightmares as the resultant unanchoring of inflation expectations would mean their loss of credibility.

As for growth-inducing factors, we know that firstly, government help during Covid had produced a fiscal impulse. Secondly, there was the spending of pent-up savings. Thirdly, the effects of reopening onto the economy and fourthly, the boost that the economy received from the easy financial conditions. Even though some of these are temporary stimuli, the effects still needed to work their way through the economy.

The lags in these effects make it doubly hard for us to gauge the resulting overall economic growth, requiring us to constantly revise our projections, as some effects come to fruition and start showing up in the data. Hence, due to these lags, “data dependency” has become the staple term for modern monetary policy-makers.

Monetary policy lags

It’s not only the stimulus effects that take time to disperse through the economy, the effects of monetary policy too take their own sweet time to course through multiple channels. Basically, there are two main stages of these time-lags, an “inside-lag” and an “outside-lag”:

The “inside-lag” comprises of “recognition-lag” and “decision-lag”, which begins with the unwarranted development (e.g. post-pandemic inflation), to the development being reflected in the data, to the decision finally taken by the Fed to undertake action (e.g. tightening). The “outside-lag”, which is also known as the “effectiveness-lag”, spans the time the measures are put into action by the Fed, to the effect impacting the banking sector, and finally, to the effect to then spread within the non-banking sector.

Note that the pass-through of the growth-inducing and inflation-inducing factors can continue to ripple across the economy and does not come to a dead stop just because the Fed has started hiking.

The “effectiveness-lag” could range from 6 months to 2 years for the whole hike to be felt by the economy, or alternatively, 4-6 quarters according to the Boston Fed President Susan Collins.

Having said that, there is a huge variation in the estimate, and considering Covid is an exceptional case, I’m guessing the lags this time could be much longer. To add, the hiking cycle happened amidst the background of many firms having refinanced before the hikes began and households amassing excess savings during Covid- among many other factors.

‘Sufficiently restrictive’ policy rate

A hawkish monetary policy conventionally lowers equity prices, strengthens the dollar and raises long-term interest rates. Through that and more, the policy causes a drag on the GDP and when this happens, the policy is considered ‘restrictive’. Technically speaking, the policy rate is restrictive when the real policy rate is above the neutral real rate.

So this begs the questions, which effects can we already see on the real economy, anecdotally or depicted in the data? Just looking at the financial conditions (e.g. long and short rate, credit spread and equity, FX), the policy rate does seem restrictive and having effect through the transmission channels. Restrictive though the policy rate may be, the question still remains, is it ‘sufficiently restrictive’ to tame inflation?

Due to the “long and variable” lags, the Fed must be part data wizard and part super-forecaster, bearing the obligation to act in a forward-looking manner. Some proposed that the Fed should act before the looked-out for (or alternatively, problematic) signs appear in the data. The argument is that if the Fed waits for the data to finally act (or alternatively, stop the actions), it might be too late.

Today, the Fed has to tread carefully as in anticipation of a slow-down in growth, it mustn’t overshoot and stall the economy or cause financial instability. On the other hand, if the Fed stops too early, inflation could still shoot upwards or harden at a level above the desired 2%. Such is the dilemma for the Fed, but what of the markets?

Stronger-than-expected growth

In a previous article I wrote, titled “The Terms of Endearment”, we covered the drivers for the term premium and how the yield curve is shaped. If you recall, the curve is formed of an expectation component and a term premium component.

What we have not discussed is what happens when market participants, just like the Fed, also have a reaction function, but unlike the Fed where its reaction function is to the changes in economic data, participants form expectations around how the Fed would react to a particular economic condition, say, to stronger-than-expected growth. An unexpected reaction towards an economic condition coming from the Fed would also promote a change in the participants’ reaction function (adaptive).

Hence, if in the context of a deeply inverted yield curve, this would amplify the change in the term premium component than would have otherwise materialised, had participants not expected a more hawkish reaction from the Fed. Alternatively, participants would conclude that stronger-than-expected growth would lead to higher inflation if the Fed decides to not do anything or that the Fed is not doing enough. Hence, participants’ confidence in the ability of the Fed to tame inflation also plays a big part.

There is a penchant for participants to take the Fed’s dot-plot as a guide for their expectations, which is surely not the intention of the Fed when publishing these. If the Fed’s dot-plot diverges from participants’ expectations, this too, may drive participants to adjust their risk premium demand. Thus, both hawkish comments from the FOMC and the publication of the dot-plot may influence the magnitude of the change in the term premium.