In a previous post from 2023 on this Substack, titled “Let’s Revise”, I wrote,

“Often times in life we need to revise our measure of a situation. The pandemic was an extraordinary, unprecedented event for which in the recent financial history, we have no comparison for. It is no surprise then that throughout the post-Covid period, time and time again, market participants have found that their various premises no longer apply.

One of the surprises is the strength of the US economy. An expectation of a recession permeated the consensus from the very beginning of the Fed’s hiking cycle and persisted well beyond the evidence of tight labour markets and growth forecasts. The thinking in the early days was that the Fed will hike, constricting the above capacity growth but pretty soon after would be forced to pivot. Lo and behold, the US economy just kept surprising us on the upside, the latest being that the US Q3 GDP grew at 4.9% annual rate, above the consensus forecast of 4.3%.”

And then, Trump became president. So, here’s “Let’s Revise II”:

Often in life, we need to reassess our understanding of a situation. The barrage of unusual Executive Orders was an extraordinary and unprecedented event for which Americans were unprepared. It’s no surprise, then, that in the post-inauguration period, market participants have repeatedly found their various assumptions no longer valid.

One of the surprises is the existence of Trump’s ‘Put’. The prevailing belief was that Trump would never take actions that might spook the markets. Yet, lo and behold, a massive drop in the S&P did not deter him from pursuing his trade war.

Recession Apprehension

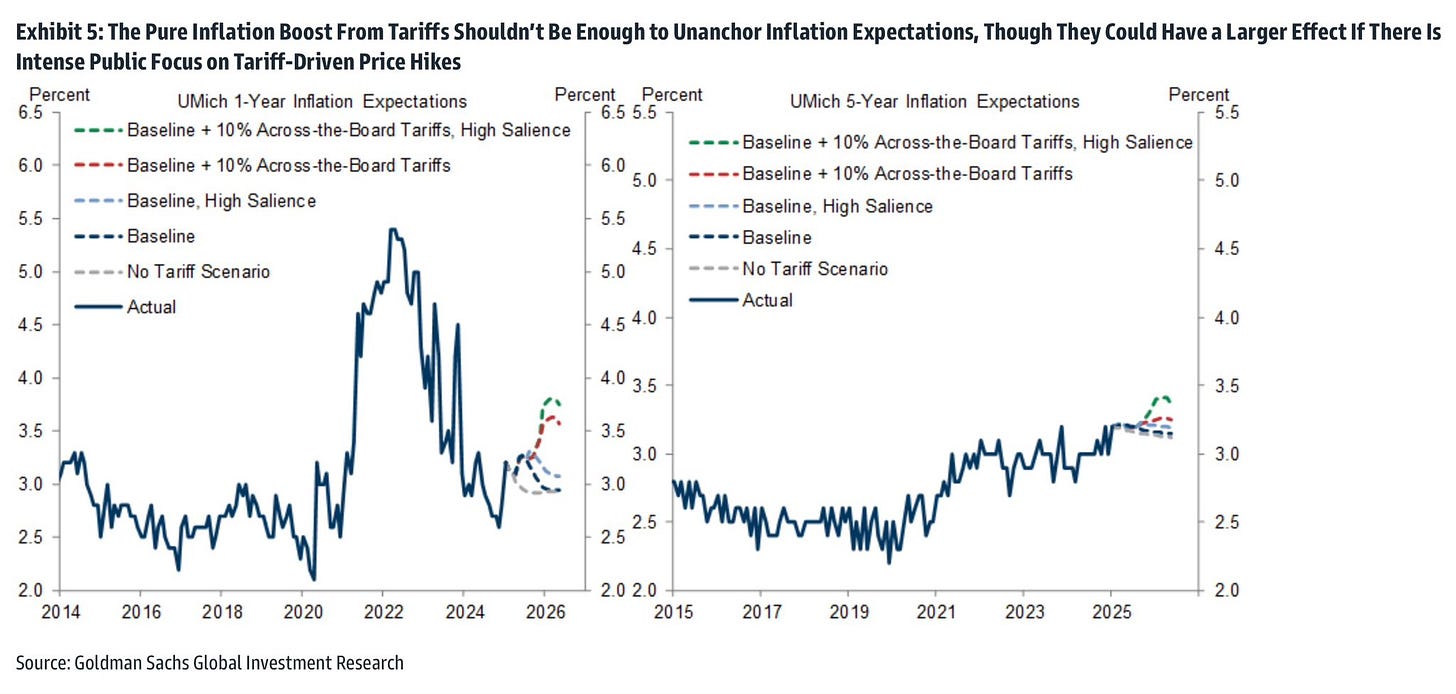

The Fed was in the process of normalising rates as inflation appeared to be trending towards 2%, with well-behaved inflation expectations. And now:

Recall that the Fed has two mandates: price stability and maximum employment. What’s a Fed to do in this situation?

To think about this, we need to consider both economic growth (the intermediate target of Fed policy) and inflation (one of the final targets of Fed policy).

What’s the possible inflation-inducing factor? Haha. Do I need to spell it out? Tariffs!

Note that the effect of tariffs on inflation and inflation expectations can be greater if everyone is focused on it. That’s the thing about expectations - it’s self-fulfilling.

By the way, I tried to tack on a 'Don’t Talk About Tariffs' day to Pi Day, but no one was enthusiastic about it. Everyone wanted to talk about tariffs instead 😔.

Countering the tariffs, consumer and corporate confidence are showing a significant decline, which may mitigate the situation somewhat. The Fed doesn’t need to wait until the actual imposition of tariffs (realised inflation) bites, as it’s already evident in inflation expectations - masses are anticipating the nightmare. The Fed wouldn’t be blamed for fearing the unanchoring of inflation expectations, though at this stage, it’s far too early to make that call. Although, given how this trade war is unfolding, expecting higher inflation for longer is probably not misguided.

As for growth-inducing factors, Trump’s administration is clearly implementing austerity measures under various guises. Additionally, the fiscal impulse from the Covid stimulus has long ebbed away, and the savings pent up during the pandemic are long spent. Most significantly, the destruction of growth propellers and networks has been set in motion, and I’m not entirely sure how Americans will repair the damage after this regime. In sum, growth is slowing down.

A condition of slowing growth and high inflation has a name, and I hope the US will be spared it through some miracle. That said, don’t jump to conclusions, as these various factors come with embedded lags and unintended consequences. As I said in January:

In an environment of chaos, it’s even more critical for the Fed to avoid knee-jerk reactions and to work with the data available, even if it’s accused of being ‘behind the curve’.

Insurance Cuts

An “insurance cut” occurs when the Fed preemptively cuts rates in response to a growth scare. This differs from a “normalisation cut”, which is carried out in response to a sufficient decline in inflation.

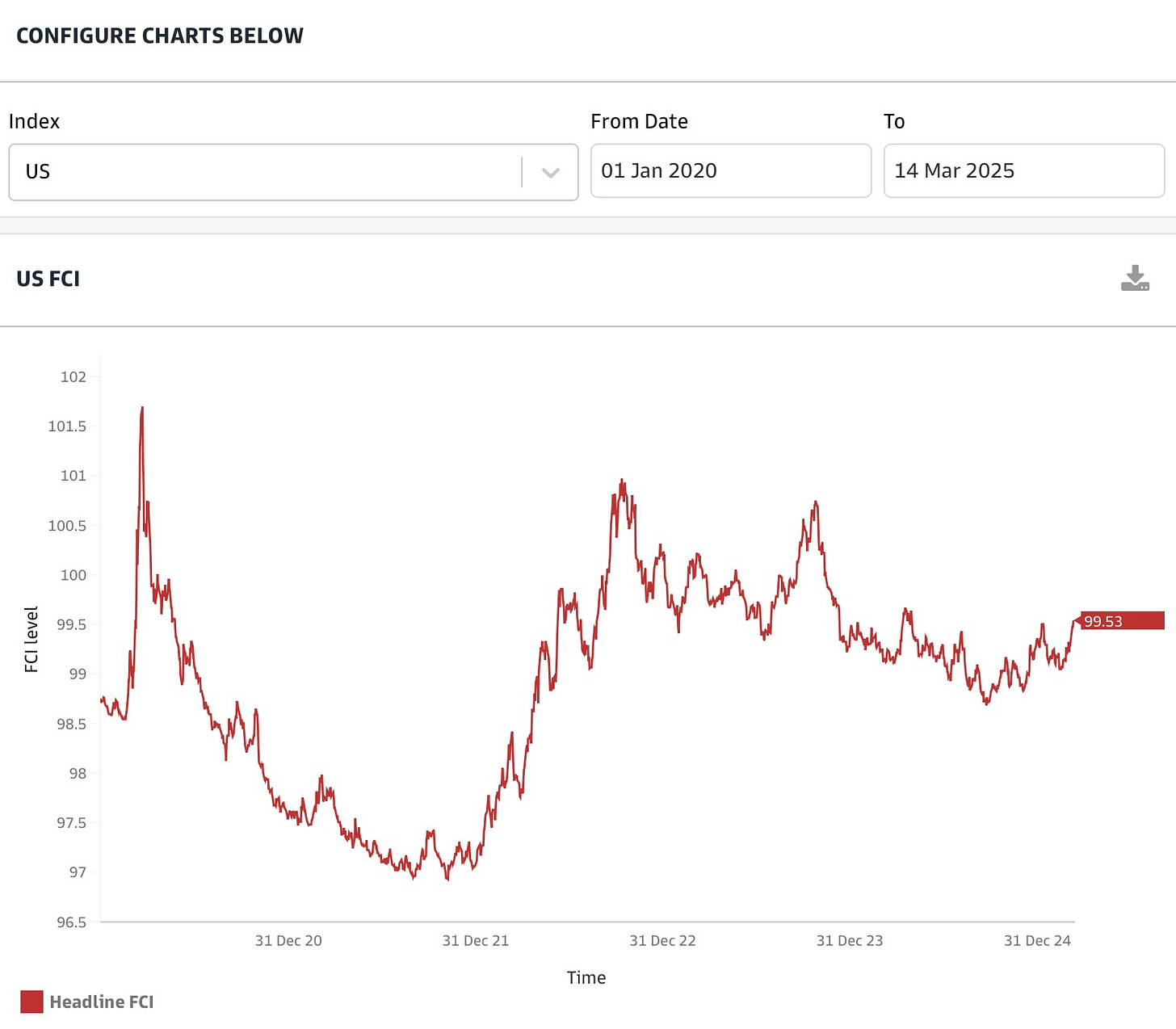

On balance, insurance policy rules do not reduce the risk of recession. While policymakers who follow such rules sometimes succeed in nipping recessions in the bud, they occasionally ease aggressively in response to a false alarm, leaving little room to ease further during an actual recession later. Moreover, insurance policy rules heighten the volatility of financial conditions and increase the risk of extremely elevated valuations.

Looking at financial conditions, Fed policy has recently become increasingly restrictive. This is something for the Fed to bear in mind when making decisions for the coming months.

The Trump Tsunami

Market participants, just like the Fed, have their own reaction function. However, unlike the Fed, whose reaction function responds to changes in economic data, participants form expectations around how the Fed might react to specific economic conditions—say, weaker-than-expected growth. An unexpected Fed response to an economic condition would also prompt a shift in participants’ reaction functions (adaptive).

This time, though, the market is also observing how Trump and his allies are managing the economy. This somewhat diminishes the Fed’s ability to shape inflation expectations. The market and the public alike have no choice but to take note of the changes, whether radical tariffs, massive sackings of federal workers, or attempts to curb immigration. As a reminder, immigration was one factor that helped ease wage inflation driven by tight labour markets.

The Fed’s options for responding to economic shocks, such as Covid or Trump (yes, I’m calling him an economic shock), differ from those in stable times and cannot be judged by the same standards. Adjusting to a shock always involves economic costs and, therefore, policy trade-offs. For instance, the Fed can adjust its lambda, which measures the weight given to output stabilisation - a trade-off between the output gap/slack and inflation. These responses aim, first and foremost, to safeguard the country’s economic infrastructure while ensuring a swifter recovery afterwards.

An example of a lambda chart:

With incomplete information ex-ante, the Fed must chart the best course to address the “Trump Shock”, which I would like to be also known as, the “Trump Tsunami”.*

During normal times, of course, monetary and fiscal policy must align with each other’s objectives. Globally, central banks have always supported fiscal policies, whether explicitly or implicitly. If unconventional policy tools lower sovereign yields and reduce government borrowing costs relative to growth rates, this, in turn, creates additional fiscal space. However, this hinges on the integrity of the Fed’s independence. Any doubt about this independence could lead to fiscal stagflation.

Having said that, monetary accommodation, when executed well, is one thing; but accommodating fiscal plans that may not deliver the promised growth is quite another.**

Fiscal plans must prove both viable and effective in stimulating growth. On the other hand, refusing to accommodate might invite accusations that the Fed is obstructing this government’s unusual policies.

*I’m calling it the “Trump Shock” because I’m shocked. Aren’t you?

**Fiscal dominance occurs when monetary policy is constrained by the need to generate sufficient seigniorage for the government to ensure its solvency.