Protectionism, specifically through mechanisms such as tariffs, can affect domestic prices in several ways. The increase in trade protectionism levels necessitates that the Fed take this into consideration when guiding policies. The ways tariffs affect prices include:

1. Increase in Import Prices

Direct Impact: Tariffs directly increase the cost of imported goods by imposing a tax on these goods. This increase in cost is often passed onto consumers, making imported products more expensive.

2. Domestic Price Adjustment

Price Matching: Domestic producers might raise their prices to match the new, higher prices of imports, especially if the imports were competitive substitutes. This happens because the relative price advantage of imports diminishes or disappears, allowing domestic producers to increase prices without losing market share.

3. Supply and Demand Dynamics

Reduced Supply of Imports: Tariffs can reduce the quantity of imports entering the market since some importers might find it unprofitable to pay the tariff. This reduction in supply, with constant or increasing demand, can lead to higher prices for goods that were previously imported.

Increased Demand for Domestic Goods: As imports become pricier, consumers might shift their demand towards domestic alternatives. If domestic production cannot immediately increase to meet this new demand, this can also lead to higher prices due to the basic economic principle of supply and demand.

4. Cost of Production

If tariffs are imposed on raw materials or intermediate goods: Domestic producers that rely on these imports might also increase their prices to cover the increased costs of production.

5. Market Structure Changes

Monopoly or Oligopoly Power: In some cases, protectionism might strengthen the market power of domestic firms by reducing competition. With less competition, these firms might have more leverage to set higher prices.

6. Currency Value Impact

Exchange Rate Effects: If tariffs lead to a trade surplus or a balance of payments improvement, this might strengthen the domestic currency, making imports cheaper in the long run, but initially, the price increase due to the tariff would still affect the domestic market.

NB: There might not be perfect pass-through of the tariff from the producer to the consumer. The extent of the pass-through depends on various market dynamics or if importers absorb part of the cost (as is frequently done in Japan).

Overall, tariffs can lead to higher domestic prices. However, the extent of this effect depends on many factors including the elasticity of demand for the goods and the competitive structure of the market.

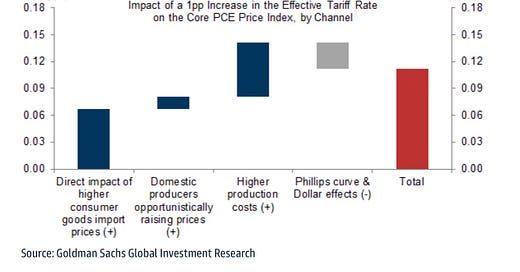

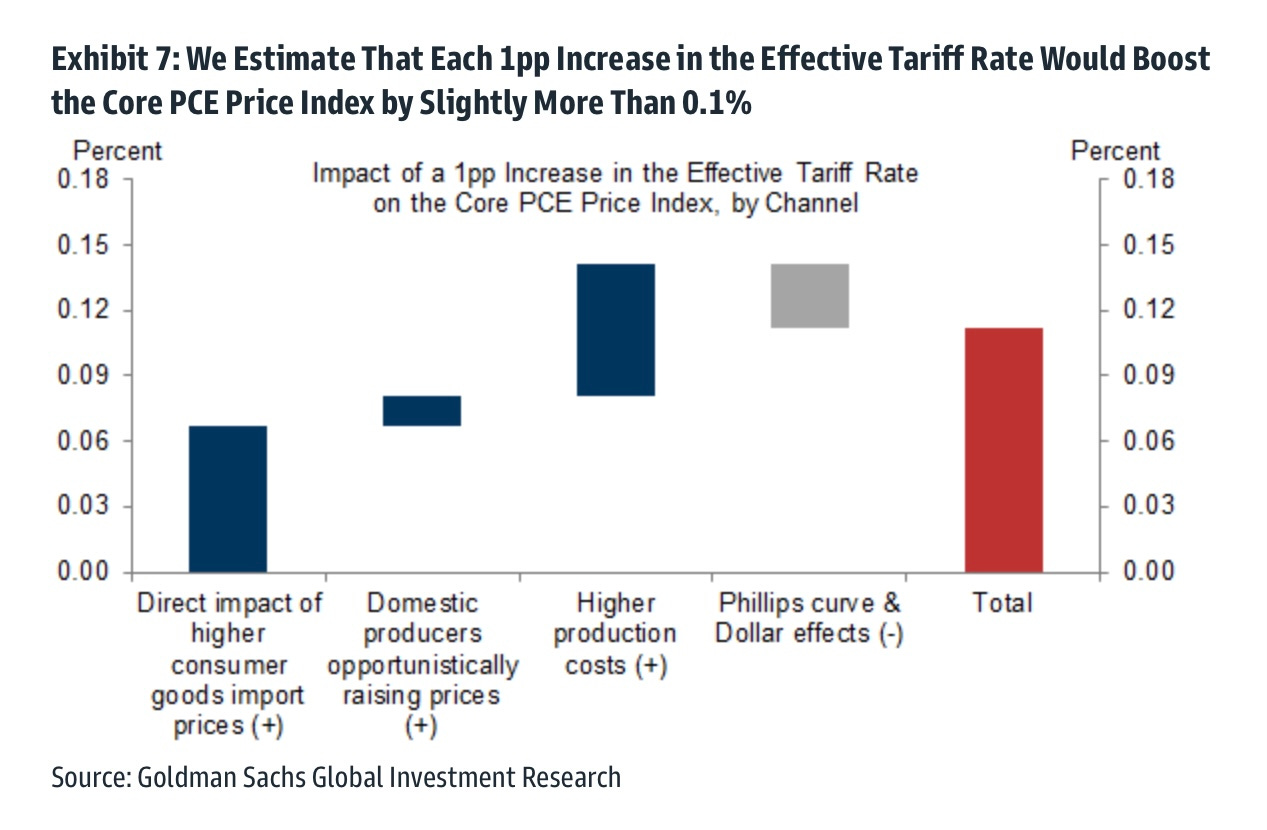

Historically, the tariff impact on consumer prices has shown to be greater than the direct effect of tariffs pass-through to consumers:

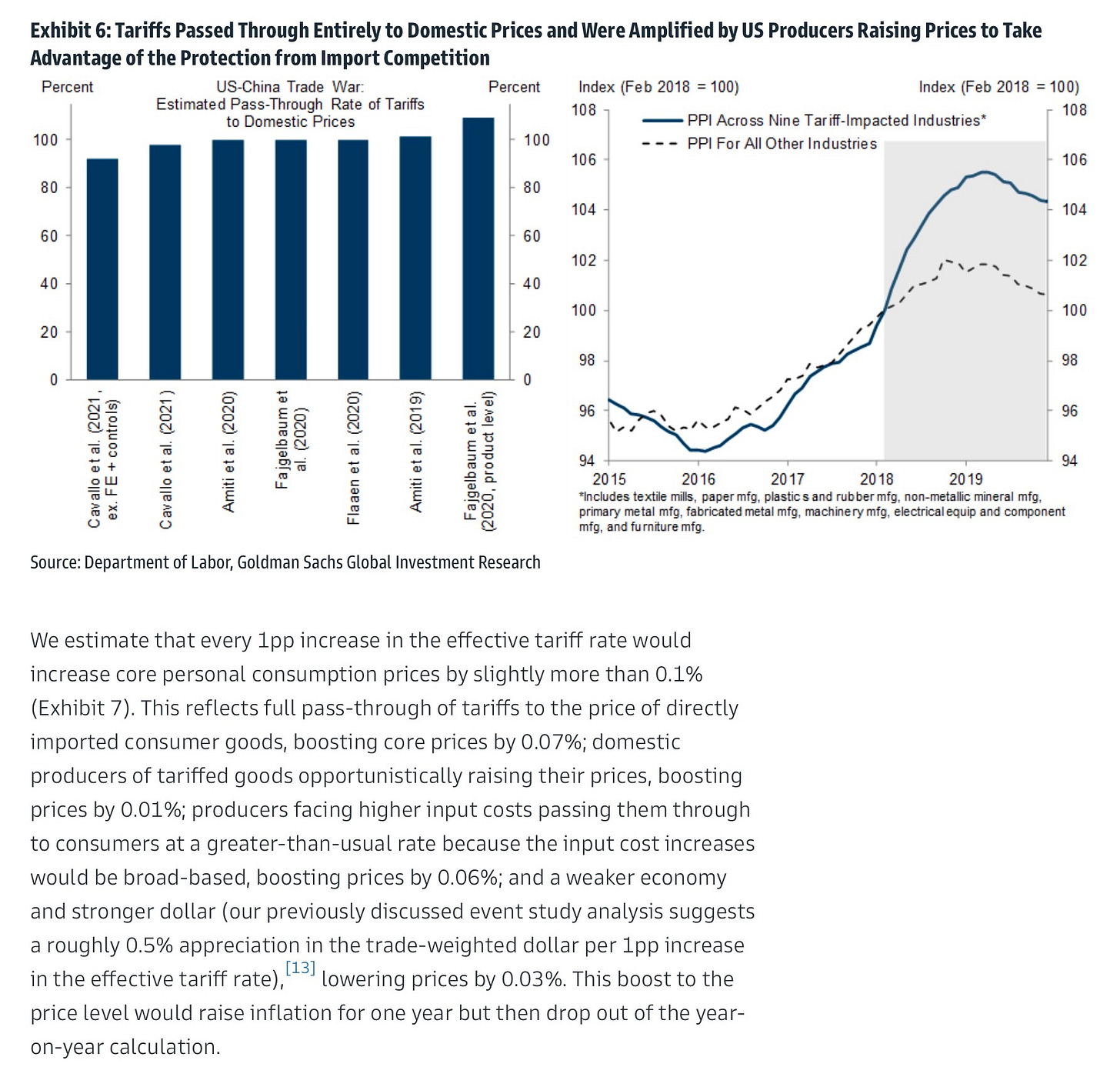

1. Based on the experience of 2018-2019 tariffs, the incidence of price increases fell mostly on US businesses and households. At the other end of the trade war, China, did not have to lower prices to remain competitive despite the rolled-out tariffs.

2. Again, based on the 2018-2019 experience, it was found that both domestic producers and non-Chinese exporters to the US market opportunistically raised their prices. In fact, some US producers responded to rising trade protections by increasing their own output prices despite an unchanged cost structure.

From a study by Amiti, Redding and Wenstein, “by December 2018, import tariffs were costing US consumers and the firms that import foreign goods an additional $3.2 billion per month in added tax costs and another $1.4 billion per month in deadweight welfare (efficiency) losses. Tariffs have also changed the pricing behaviour of US producers by protecting them from foreign competition and enabling them to raise prices and markups…the combined effects of input and output tariffs have raised the average price of US manufacturing by 1pp…”

Despite the study findings, the overall impact on general inflation was modest because tariffs affected only a portion of imports. In addition, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) data from that period does not show a significant spike in inflation directly attributable to tariffs. Inflation remained relatively low, with the U.S. experiencing inflation rates around 2% or less, which was in line with the Federal Reserve's target. This suggests that any inflationary pressure from tariffs was either absorbed by other economic dynamics such as domestic production, low global inflation, stable oil prices, currency movements and counteracting monetary policy at the time; or was not significant enough to stand out against other factors.

How reliable is the period 2018-2019 as guidance for 2025 onwards? It depends. In the previous period tariffs were targeted, whereas this time, Trump is talking about blanket tariffs on a larger scale. Is this just rhetoric or for real? With Trump, who knows? Admittedly, over 2,000 product-specific exclusions were granted during the 2018-2019 tariff rounds. Some imports from China were also redirected through other countries, escaping the tariffs on Chinese goods. So there are reasons to think that the effective tariffs in the end will not be as great.

If the assumption that Trump’s tariffs are more bark than bite, then the Fed presumably will not have to take the trade war (tariffs, including the retaliation by other countries) much into account. However, should Trump Tariffs 2.0 prove to be chaotic, introducing much uncertainty into the economy and affecting inflation expectations as well as increasing the risk premia due to uncertainty, then this is something that should make the Fed tread with caution. This is especially so in the next few years as the Fed is in the midst of normalising its rates.

In a way, you’ve got to pity the Fed. As they were just about to take a victory lap from having tamed post-Covid inflation, here comes another uncertainty in the form of radical government policies. Or, quoting Waller the other day, “Overall, I feel like an MMA fighter who keeps getting inflation in a choke hold, waiting for it to tap out yet it keeps slipping out of my grasp at the last minute. But let me assure you that submission is inevitable - inflation isn't getting out of the octagon.”

I don’t share Waller’s optimism because I don’t know yet know how effective and serious the new government will be. The only constant between this presidency and the last one is Trump himself as many of the players in charge the last time have been changed.

Due to the uncertainty, prudence dictates that the best course of action for the Fed is not to anticipate economic outcomes from the fiscal policy side but rather stick to being data dependent, gradually moving towards the optimal rates.

To add, according to the snips from Goldman Sachs above, “this boost to the price level would raise inflation for one year but then drop out of the year-on-year calculation”. If protectionist actions are merely transitory, then there is strong cause for the Fed to “look through” the event. Looking through transitory inflation is good practice for central banks.

As Powell stated last month, “We don’t guess, we don’t speculate, we don’t assume,” which is perhaps the right stance if the Fed wishes to retain its reputation as an independent and non-political institution. The moment the Fed starts anticipating government policies, this can be interpreted as accommodating or complicating the execution of fiscal policies. Such actions could create doubt about the Fed’s independence, potentially leading to fiscal stagflation.

Having said that, from the perspective of the entity tasked with managing inflation expectations after a series of unwarranted fiscal stimuli and erratic trade policies, it naturally makes sense to consider the probable actions of the new government and maintain a defensive stance. Or, in Waller‘s terms, “be ready with the choke hold”.