Monetary Policy in Times of Dollar Dominance

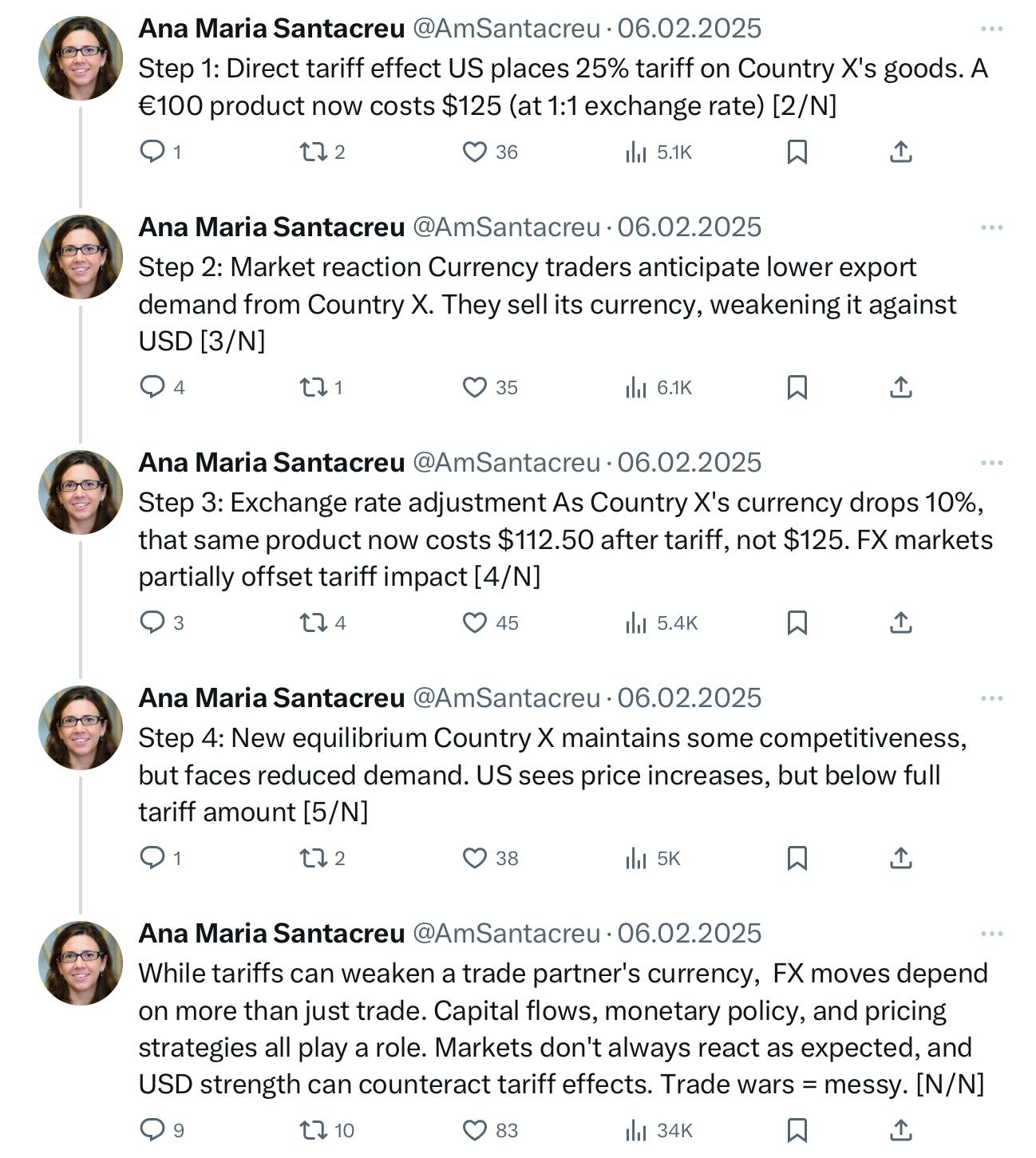

Previously, we discussed monetary policy during times of protectionism. A natural extension of this discussion is: what happens when a country takes a step further and intervenes in the value of its currency?

Currency movements and exchange rates directly influence the prices and volumes of imports and exports. Depreciating a country’s currency makes its exports cheaper, thereby increasing their competitiveness in the global market compared to goods from other countries.

Currency depreciation is also a contentious topic among nations, as exchange rates can force shifts in monetary policies. For the United States, currency values have become a more prominent factor in the Federal Reserve's reaction function, primarily because fluctuations in the dollar affect US financial conditions through various channels.

In recent years, the effect of foreign exchange (FX) on the Financial Conditions Index (FCI) has become more significant, with tighter financial conditions often resulting from a stronger dollar and looser conditions from a weaker dollar.

However, before delving too deeply, and considering that this Substack primarily focuses on US monetary policy, let’s start with a primer and examine the dollar and the outsized role it plays in global economies.

The Dollar Dominance

"Dollar dominance" refers to the dollar's extensive influence in global trade, where over half of all trade is invoiced in dollars and approximately 60% of global central bank reserves are held in dollars.

Its other significant uses include borrowing, where foreign entities often borrow in dollars to hedge against foreign exchange risk; payments, where 58% of international payments (excluding those within the Eurozone) are made in dollars, alongside its use in forex transactions; and as a store of value, where the dollar serves as a safe haven, offering both credibility, liquidity and convenience.

Additionally, during financial crises, the Federal Reserve extends swap lines to other central banks, reinforcing the dollar's role in global financial stability.

The Strong Dollar and Trade

Theoretically, for consumers who buy foreign-made goods, a strong dollar means cheaper imported goods due to favourable exchange rates. In practice, the impact on import prices is less substantial than one might expect. This is largely because most US trade is conducted in US dollars, leading foreign suppliers to maintain their prices despite fluctuations in the dollar's value. Consequently, the benefit of lower import costs to combat inflation is somewhat limited. If the dollar unexpectedly and significantly depreciates, US imports will likely remain unaffected, and the terms of trade (the ratio of export prices to import prices) will not worsen.

For producers who wish to export, a strong dollar makes their products relatively more expensive than those of foreign competitors, reducing their competitive advantage. US export prices are more significantly impacted, as the trade balance adjusts primarily through fluctuations in export prices when the dollar strengthens. This makes American products pricier overseas, potentially decreasing demand for US exports.

However, the relationship between exchange rates and export volumes is more complex than described above due to Global Value Chains (GVCs). This complexity arises from several factors:

Foreign Value Added: When the proportion of foreign components in exports rises, the impact of exchange rate changes on export competitiveness diminishes. A large part of the export price is influenced by costs in foreign currencies, meaning a weaker dollar does not enhance competitiveness as much as expected.

Return Domestic Value Added: When exports are re-imported for further assembly or use in the home country (or in countries using the same currency), currency devaluation does not significantly stimulate these exports because the final market is unaffected by the currency change.

Intermediate Value Added: Exports intended for further processing abroad respond more to the exchange rates of the countries where they will be re-exported, rather than the initial exporting country's exchange rate.

Due to increased involvement in GVCs, certain industries may experience a decrease in export volumes after a currency depreciation. This complexity affects how we understand and model trade policies and macroeconomic effects, suggesting that traditional models may overestimate the influence of exchange rate movements on exports in a world dominated by GVCs.

What about companies that operate both domestically and abroad? A strong dollar can lead to lower earnings for multinational companies in the S&P 500, as their foreign earnings are worth less when converted back to dollars. This can negatively impact stock market performance, reducing wealth for investors.

A strengthening dollar may also put downward pressure on the prices of essentials such as oil and other commodities, which in turn affects consumers and exporters.

Currency Manipulation

Now that we’ve explored how currency value affects the movement of goods, let’s examine how currency manipulation influences the movement of capital.

Currency manipulation, in brief, occurs when a country directly intervenes in foreign exchange markets to alter its currency’s value, aiming to boost competitiveness and improve trade flows. While the term carries a negative connotation, in a broader context, it is entirely legitimate for countries to use macroeconomic policy levers for reasons they deem appropriate. This is part of their sovereignty, except in cases where they are bound by agreements or pacts with other countries.

For a long time, the US has regarded certain countries, particularly China, as currency manipulators and has sought to include restrictions on such practices in trade agreements with these nations.

The US has also been accused of starting a currency war. In November 2010, it launched a massive asset purchase program dubbed QE2, worth $600 billion, to stimulate the American economy. This flooded global markets with liquidity, affecting emerging economies.

By attempting to lower US long-term interest rates, this policy was likely to trigger capital outflows, leading to a depreciation of the dollar. This, in turn, would exert upward pressure on emerging market currencies. Consequently, these markets might experience capital inflows, which could abruptly reverse when conditions change. Such a sudden reversal would ultimately devalue emerging market currencies—an outcome that is highly undesirable.

Moreover, emerging economies worry that large capital inflows could lead to unsustainable credit expansion in their financial sectors. To make matters worse, these economies often lack the tools to effectively counter speculators and prevent such inflows.

On the other hand, regarding capital outflows, Ben Bernanke’s taper tantrum in 2013 saw US long-term rates rise by over 100 basis points, spurring significant capital outflows from emerging markets. Some highly vulnerable countries found themselves in serious trouble during this period.

China

The US has been concerned that China is depreciating its currency to promote growth and maintain its significant current account surpluses. While this could be viewed as manipulation, other factors at play suggest a more complex story.

In 2015, for instance, the US economy was recovering strongly. Most members of the Federal Reserve and the Federal Open Market Committee expected to begin raising interest rates in the second half of the year. However, in August, China devalued the renminbi, causing turbulence in global financial markets. Concerns about potential further devaluations grew, leading to falling stock prices, widening credit spreads, tightening financial conditions, and heightened worries about weak global growth for Fed policy. As a result, the Federal Reserve decided to forgo an interest rate increase in September, which most had expected to occur.

How the Dollar Reacted to the Tariff Announcement Chaos

Initially, the US dollar exhibited a consistent reaction to substantial tariff threats, though the market had not fully priced in the deeper risks associated with these tariffs. Consequently, upward movements in the dollar remained the most effective hedge against anticipated tariff risks.

Second, the peak gains in the dollar were not as high as expected. This discrepancy can primarily be attributed to investor skepticism—correct in retrospect—regarding the persistence of these tariffs, and secondarily to the stability of the Chinese yuan (CNY) fixing rate during this period.

(However, if the tariffs persist for an extended duration, these effects will converge toward a higher level. While a steady CNY fixing rate and a less-than-proportional tariff response from China may suggest a more conciliatory stance, this posture could shift if tariffs remain in place over the long term, potentially amplifying economic tensions.)

Third, even if tariffs are used strategically to extract concessions, the uncertainty they generate is likely to exert downward pressure on trade-dependent economies and disrupt capital inflows into the Euro area and China. This uncertainty may also delay Federal Reserve action, as the inflationary consequences remain ambiguous, thereby maintaining wide interest rate differentials.

Finally, the robust US payrolls report underscores that underlying economic performance continues to provide a foundation for dollar strength. While we should remain attentive to risks from tariff effects or global economic growth, the US economy currently sets a formidable benchmark. This dynamic is likely to sustain dollar strength over an extended horizon.

Spillovers

By now, you may have noticed what I’m trying to do. In previous posts, I focused solely on monetary policy in a domestic setting, but I’ve been subtly shifting the discussion to show that US monetary policy (and that of other developed countries) generates spillovers, meaning it impacts other countries’ monetary policies.

It’s important to understand that the spillover effect differs between small, open economies and large, closed economies. (The US, by the way, is a large, closed economy.) It’s helpful to think about monetary policy spillovers in terms of the various channels of the transmission mechanism. The full impact of each channel varies from country to country, depending on how sensitive their economies are to changes in these channels.

For small, open economies, the “exchange rate channel” is a key consideration for monetary policy. A fall in the central bank’s key interest rate relative to rates in other countries makes domestic assets less attractive to investors, triggering capital outflows and depreciating the home currency. This depreciation raises the price of imported goods or makes domestic goods more competitive in foreign markets (a phenomenon known as foreign exchange pass-through).

For large, closed economies, the “expectations channel” influences saving-investment decisions, asset prices, wages, and the prices of goods and services. In these economies, domestic markets primarily drive monetary policy outcomes. The speed and effectiveness of policy actions depend on the efficiency of these markets.

For countries with dollar-denominated liabilities, a depreciation of the home currency increases the burden of these liabilities.

Historically, the US has been largely immune to cross-country spillovers. In contrast, emerging market rates must respond to US policy tightening. The degree to which emerging market economies can temporarily ignore US monetary policy in pursuit of their own objectives reflects the policy lags in those countries.

In fact, there is significant variation in how advanced and emerging economies respond to US interest rate surprises. When responding to US tightening, GDP in foreign economies declined as much as in the US (see Iacoviello and Navarro, 2018), with larger declines in emerging economies than in advanced ones.

In advanced economies, the level of trade openness and the exchange rate regime account for much of the contraction in activity. In contrast, in emerging economies, responses do not depend on the exchange rate regime or trade openness and are larger when vulnerability is high.

Central Banks Coordination

Coordination can be defined as a set of policy changes that benefits all countries. More formally, coordination is possible when the decentralised equilibrium, or Nash equilibrium, can be made more efficient.

From Olivier Blanchard’s paper, under this interpretation of coordination, the general answer is straightforward and well-known: if countries have as many non-distorting instruments as they have targets, the Nash equilibrium is efficient, and coordination cannot yield a better outcome for all countries. (Targets may include the output gap, inflation, exchange rates, and financial stability, while instruments could include monetary policy, fiscal policy, macroprudential policy, foreign exchange intervention, and capital controls. Some policies serve as both instruments and targets, increasing the number of targets and potentially creating distortions.)

A broad discussion of whether countries have as many instruments as targets can become abstract and unproductive. Simply counting instruments and targets is unlikely to resolve the issue because some policy instruments may introduce distortions, thus functioning as both targets (to minimise distortions) and instruments. If all instruments are distortionary, for example, there will always be more targets than instruments, leaving room for coordination to improve outcomes. However, if the distortions are minor, the benefits of coordination may be limited.

Should The US Be Concerned About The Global Impact of Its Monetary Policy?

The counterargument from the US is that, while downward pressure on the dollar may harm other countries, it also strengthens the US economy. Strong US economic growth, in turn, fosters robust global economic growth.

Spillovers can also lead to spill-backs, where a struggling global economy depresses US economic growth. Therefore, supporting foreign economic policy is generally advantageous for the US economy as well.

During the Asian financial crisis in 1998, Alan Greenspan wanted to cut rates despite strong US growth. He argued, “It’s just not credible that the US can remain an oasis of prosperity unaffected by a world that is experiencing greatly increased stress.”

The situation today is somewhat similar but also different. US growth is once again roaring. The US is in the process of normalising its rates after successfully combating high inflation. However, political events and broader uncertainties—not just tariffs—have collided with this reality, pushing the Federal Reserve into a holding pattern. It is keeping rates high and delaying further cuts until the economic landscape becomes clearer.

The Fed in Times of Crisis

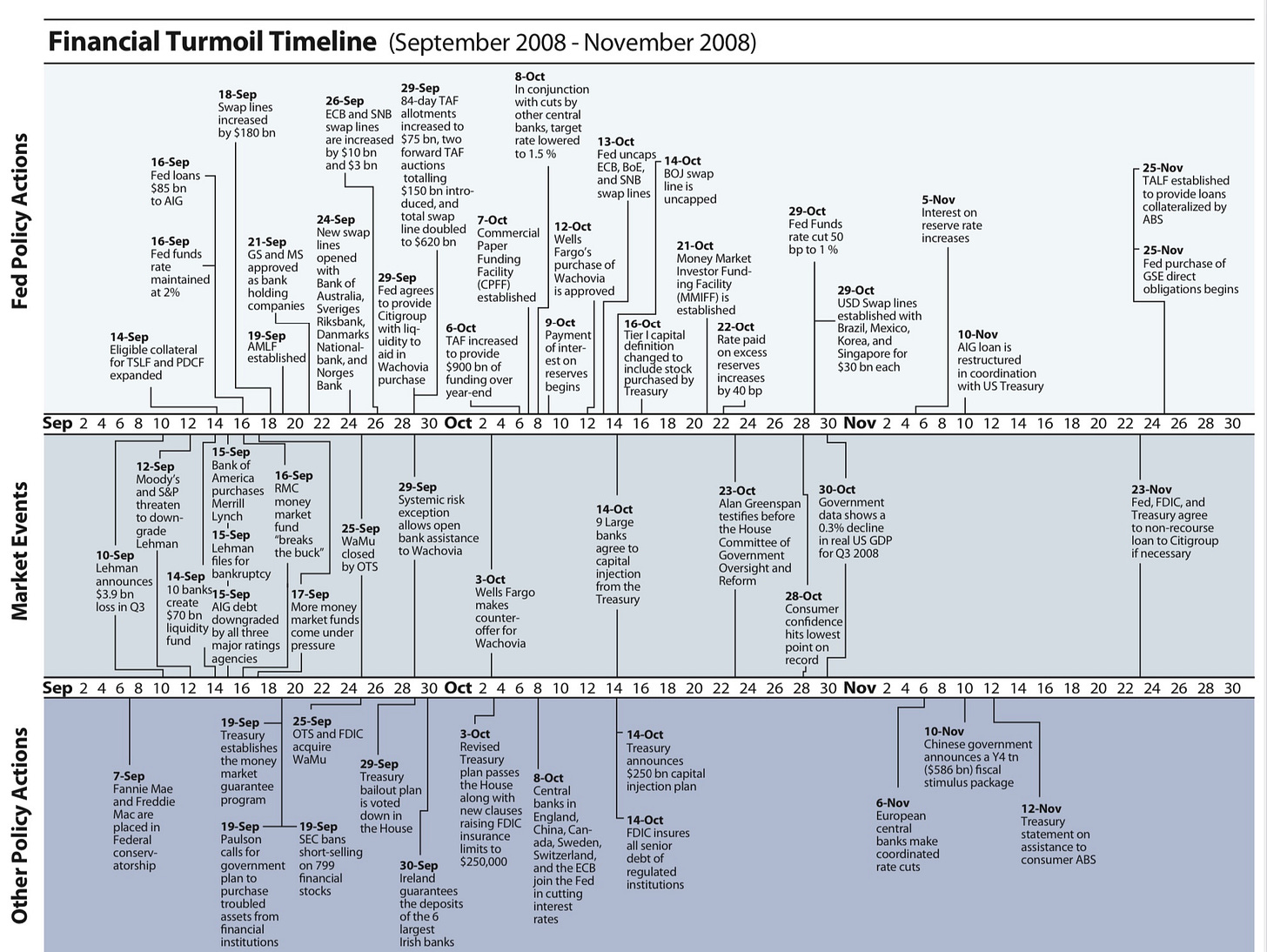

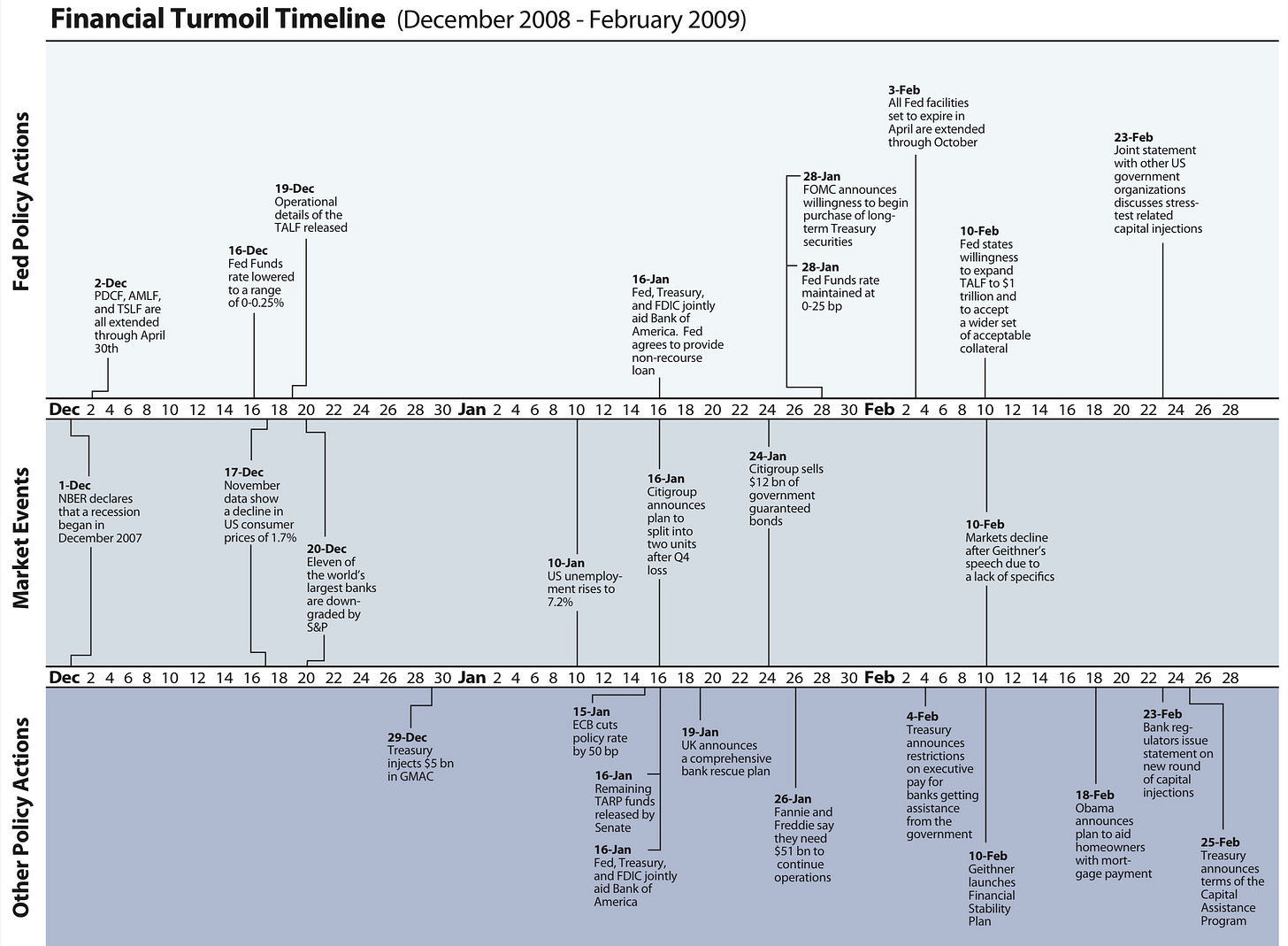

In December 2007, the Federal Reserve announced its first swap lines with the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Swiss National Bank. In September 2008, after Lehman Brothers’ collapse, the Fed responded to requests from other central banks by activating swap lines to provide liquidity to banks engaged in dollar-based finance. In October 2008, the Fed established swap lines of $30 billion with the ECB and $15 billion with the Bank of England (BOE), among others. In December 2008, the Fed announced unlimited swap lines with the ECB, the Bank of Japan (BoJ), and the Swiss National Bank to ensure adequate dollar liquidity.

These actions demonstrated unprecedented international cooperation among central banks, reminiscent of a time when America was seen as a caring global leader. Today, with “America First” as the nation’s prevailing mindset, it’s unclear whether we could maintain the same financial stability if another crisis were to erupt.

https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/global_economy/policyresponses.html