“Perhaps a complex offer by the central bank to buy and sell at stated prices gilt-edged bonds of all maturities, in place of the single bank rate for short-term bills, is the most important practical improvement which can be made in the technique of monetary management”

~ Keynes (1936)

Kon’nichiwa…

The Bank of Japan is expected to discontinue its negative interest rate policy and yield curve control soon, so I thought we could take a detour in our exploration of the US monetary policy for me to write a bit about it.

The types of policy employed by the BoJ can be listed as forward guidance, negative interest rate, yield curve control and asset purchases.

In 2008, the BoJ began the Complementary Deposit Facility, paying the interest on excess reserves (IOER) and setting the rate for the facility at 0.1%. This is called the Quantitative and qualitative monetary easing (QQE). Fast forward to 2016, the BoJ added the Negative Interest Rate Policy (NIRP) to the QQE, keeping the short-term policy interest rate at -0.1% and the 10-year yields around zero (-0.1% to 0.1%). The IOER is considered as the floor for this interest rate corridor. The BoJ set up a program of fixed-amount bond auctions as well as “Sashi-Neh”, the 10-year JGBs purchases at a fixed price for an unlimited amount.

Regarding the corridor, the BoJ is in effect implementing a three-tier framework where the negative rate is applied to the policy rate balance. The three-tiered structure of the BoJ’s current account balances looks like this:

Post-NIRP discontinuation, the BoJ would probably change the three-tier to a one-tier structure, with a single interest rate on the excess reserves (IOER). This can act as a strong signal that the BoJ has no intention of reverting to the NIRP should the economy struggle.

The yield curve control (YCC) was also added to the QQE in 2016. Ever since the US Federal Reserve System tried to support bond prices in the 1940s, no other central banks have attempted any form of YCC until Japan in 2016 and the Reserve Bank of Australia in 2020.

YCC targets or caps one or more specific yields via announcement and purchase effects. Bernanke came up with the idea of “announcement effect”, a conjecture that the BoJ is able to moderate purchases needed just by announcing the introduction of the YCC. Not scheduling the purchases is a feature of the BoJ’s YCC. Today, the general expectation is for the BoJ to discontinue YCC targets for the 10-year JGB rate (i.e. 0% target interest rate and the +1% reference rate).

The aims of the BoJ’s YCC include:

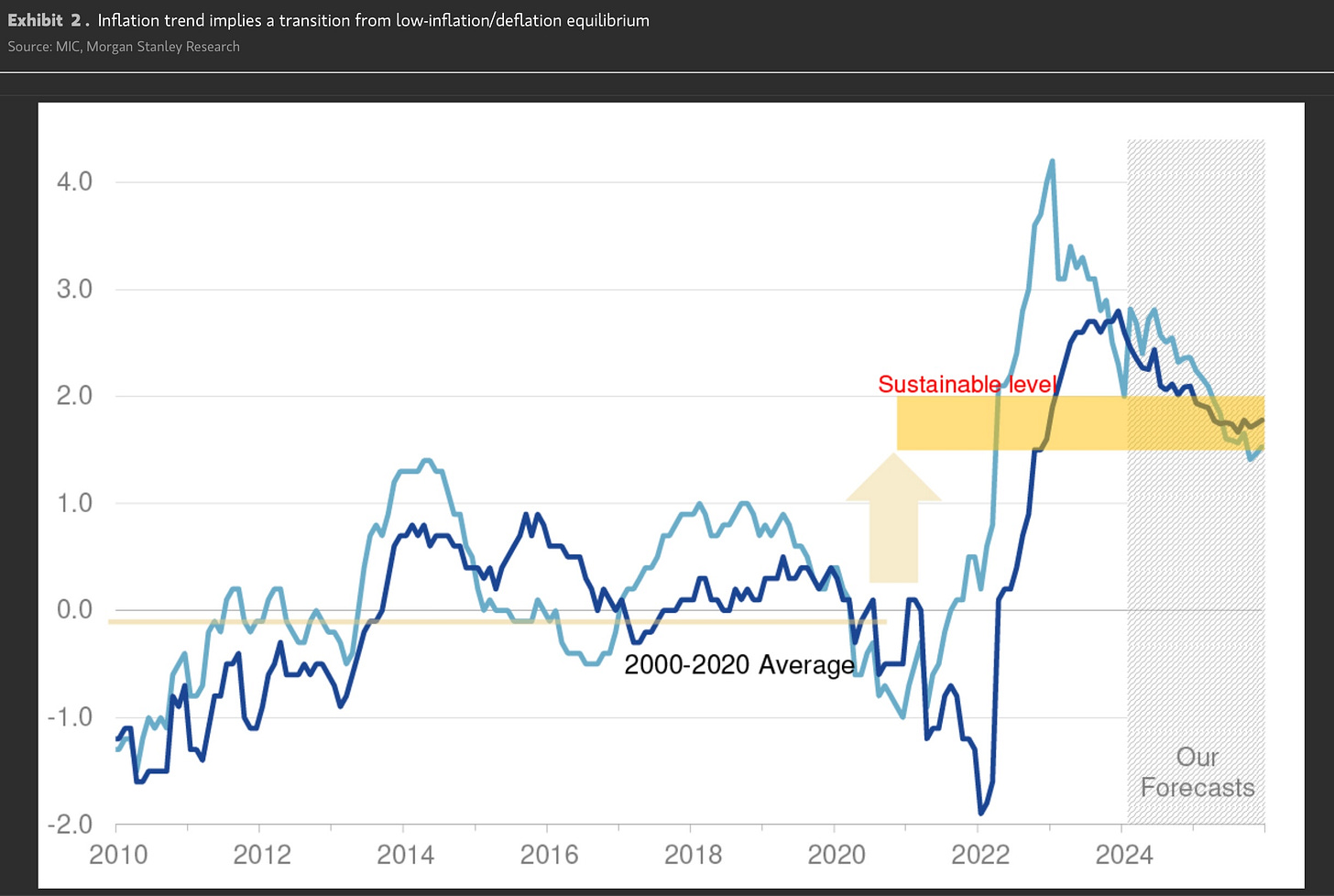

Japan has adaptive inflation expectations (see previous post on inflation expectations). Therefore, maintaining an output gap in the positive territory for a period of time, for as long as possible, would help the BoJ get to the 2% target (price stability).

Understanding that quantitative easing carries with it positive and negative consequences, the ability of the central bank to mitigate the negative consequences by controlling interest rates is beneficial.

A commitment to overshoot inflation could strengthen the forward-looking feature of inflation expectations.

So now, we have QQE + NIRP + YCC, an interesting bundle that forms the framework of the BoJ policy.

Why was the BoJ forced to take this action? In short, they have exhausted the effectiveness of quantitative easing, suffering from lethargic inflation while the economy stayed in the doldrums. Even after all this, inflation remained unresponsive, causing the BoJ to extend the length of the policy. The unexpected consequence of dwindling trading volume propelled the BoJ to widen the range in order to bring trading up (see Table 3 below).

Regardless, once this framework ends, Governor Ueda will have to rely even more on forward guidance. How Ueda-san would do this is still unclear. Most likely, the BoJ will remain flexible in its methods. Having said that, the policy would likely continue to be easy for some time even though in the longer run, the BoJ would want to reduce its JGB holdings. The reduction will become possible once the BoJ could remove the phrase, “will not hesitate to take additional easing measures if necessary” from the Bank’s communication for good. There is hope for this to happen if we look at the inflation and wage growth trends.

When exactly the BoJ would exit its policy depends partially on wage events and these include the Shunto spring wage negotiations that just concluded yesterday (the union federation says members secured an average hike of 5.28%, the most in 33 years) and the wage hike rate for services (coming, 4th April).

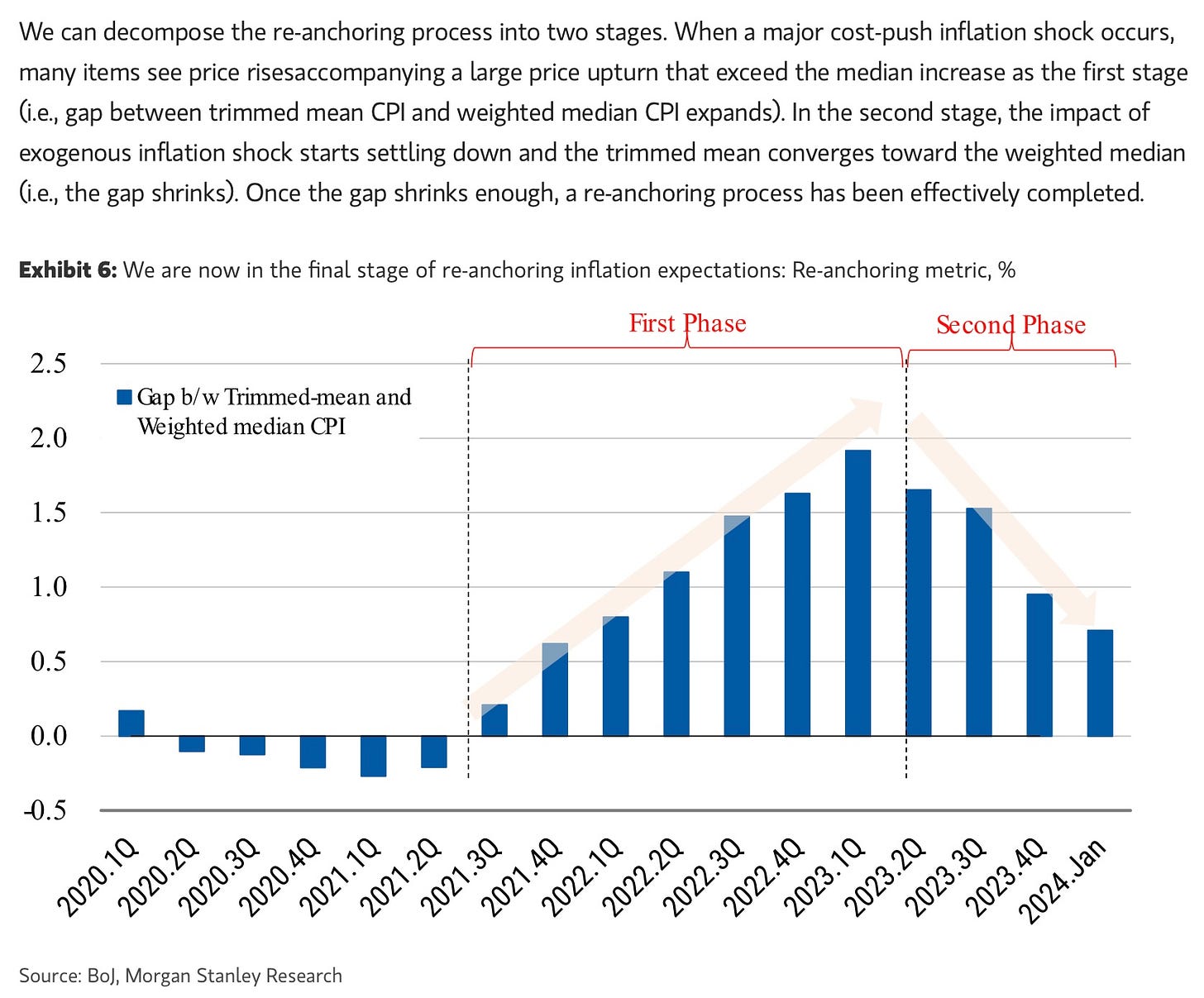

Increases in wages may be passed on to prices (wage-price pass-through, or in the BoJ’s words, “virtuous cycle of wages and prices”). This will strengthen the case to stop the policy. In addition, Japan’s version of the core CPI has remained +2% YoY or more for 22 consecutive months. The reanchoring of inflation expectations has also strengthened, which should lead to a reinforcement of the wage-price pass-through effect.

The next few years should be interesting to watch as Japan begins its normalisation policy.

Nice blog! thanks

How can rates be normalised considering JP debt to GDP ratio is over 260%, prolonged normalised interest rates would result in interest payments ballooning to over 50% of government revenue over time. Is there a way out?