The Market’s Terms

Why do we pay so much attention to Treasury securities? (Please skip this part if you already know).

From the yields, we derive the interest rates for the valuation of other securities as well as benchmarking other non-Treasury securities. From those Treasury yields too, we are able to compare the relationship between “on-the-run” Treasury yield curve (most recently auctioned) and the term structure of interest rates, i.e. the term structure of interest rates shows the relationship between the theoretical yield on zero-coupon Treasury securities and maturity. From this, we can derive the value of fixed-income securities using the zero-coupon Treasury security, otherwise known as the Treasury spot rate.

The US Treasury issues securities that are backed by the credit of the US government and is regarded as default-free and risk-free. Having said that, there are still risks that come with these securities which include interest rate risk, yield curve risk, liquidity risk, exchange-rate risk, volatility risk, inflation/purchasing power risk and event risk.

Studying fixed income, we are introduced to the term structure of interest rates theories which explain how the shape of the yield curve came to be. A normal yield curve is usually an upward sloping curve. An inverted yield curve shows that the yield gets lower as the maturity increases. A flat yield curve on the other hand shows the same yield regardless of maturity. The shape of the yield curve changes over time in response to a variety of things.

There are three dominant term structure theories; A) the pure expectations theory, B) the liquidity preference theory and C) the market segmentation theory.

A. The pure expectations theory describes the term structure as the expected future short-term interest rates. For instance, the market will set a two-year bond yield to be equal to the return of a one-year bond plus the expected return of a one-year bond bought one year from today. Hence, a flattening term structure according to this theory means an expectation that the future short-term rates will be unchanged from today’s short-term rates.

B. The liquidity preference theory states that investors would demand compensation for the interest rate risk that comes along with holding longer-term bonds. This is because the price becomes more volatile when interest rates change, and this price volatility is greater the longer the maturity. Therefore, according to this theory, the term structure is composed of expectations of future interest rates plus an interest rate risk premium and this premium increases with maturity. Hence, if the yield curve is flat or downward sloping, the theory forecasts that the future short-term interest rates will fall.

C. The market segmentation theory states that the supply and demand for funds for each maturity sector of the yield curve determines that sector’s interest rate. These sectors exist because of the different needs of bond investors, e.g. ‘managing funds vs market index’ or ‘managing funds vs liabilities’. There is an off-shoot of this theory called the ‘preferred habitat theory’ which you can look up if interested. I would recommend the book by Frank Fabozzi entitled “Fixed Income Analysis” for further reading on this subject.

Irving Fisher’s hypothesis is that interest rates are formed from the sum of real rate of interest plus the expected inflation premium (risk that the inflation rises). Hence, a downward sloping term structure means that investors are expecting future inflation to decline. (Alternately, a humped term structure means investors expect a rise for a few years, then a fall for a few years). The natural extension to this thinking then is, what is the neutral short-term real interest rate?

The risk-neutral expectations move closely with the policy rate. However, this relationship weakens as the tightening cycle progresses. To estimate the long run expectations embedded in the curve (i.e. the investors’ version of the neutral rate), we can use the 5y1m and 10y1m Overnight Index Swap (OIS) forwards while adjusting for the matched term premium estimates from the Treasury curve. (An alternative is to use the forward risk-neutral yield estimates from the Treasury curve.) Note that using different models will compute different neutral rates. Presently, there is a belief that the neutral rate is actually higher than what was previously thought.

Perhaps these theories could help us in understanding the recent behaviour of the Treasury yield curves. Keep in mind that today, these theories need to be seen in the context of the Fed tightening cycle.

The Term Premium

The term premium is the additional yield that the market requires to compensate for the risk that the path of short-term rates may diverge from expectations. It is a display of the uncertainty borne by investors about the progress of economic growth, the inflation path, as well as the reaction function of the Fed. In other words, the term premium is the investors’ compensation for holding duration risk.

The estimation of the term premium can be carried out via 1) calculating an historical ex-post total return on a long-term bond minus total return on a short-term bond, 2) employing surveys of predicted policy rates, and 3) using asset pricing models. (The last one having the advantage of market prices as direct inputs and can be updated frequently in real time.)

The term premium today is rather low compared to most of its recorded history. Other than in the late 70s and early 80s, the term premia have fallen during policy tightening, with the magnitude being greater the more orderly the rate hike cycles were. One reason why this could be is because investors are less risk averse during expansions. In addition, tightening lowers the medium term inflation risks, as well as the existence of good economic conditions that makes tightening possible would then produce lower asset volatilities. In contrast, the late 70s and early 80s saw investors not entirely sure that policy tightening would mitigate the medium term inflation risks.

After a sharp fall during the GFC, short-term rate expectations have been largely stable. This points to the fact that fluctuations in rates are mainly attributable to the adjustments in the pricing of the term premia. For example, the ‘taper tantrum’ in 2013 when bond yields rose may have been caused by a change in the term premia rather than short rate expectations. Throughout 2017, regardless of rates hikes, the term premia fell, which drove the rally in the long-term Treasury bonds. The low term premia may have resulted from the low uncertainty about inflation. The end of the period of low uncertainty, i.e. the dispersion of investors’ inflation views in surveys, would mean a higher term premia.

In the instance where the term premia do not agree with the fundamentals, domestic quantitative easing or foreign influence may be the reason. Together, surging deficits and the Fed balance sheet run-off can result in an increase in Treasury issuance to the public, putting an upward pressure on the term premium via a supply effect. Furthermore, surging deficits impact long-term rates in two ways, first, there is a monetary policy response to the boost to aggregate demand and second, a bigger premium is demanded by markets to absorb the increase in the supply of Treasury debt.

Alternately, there may also be a degree of term premium spillovers that lift the term premia across integrated capital markets. The ECB and the BoJ may in return, also influence the pricing of the US Treasury term premia through their own monetary policies. In addition, the pandemic shock has affected economies globally and prompted identical responses from central banks. This gives rise to correlation in responses, especially in short rate expectations. In support of these observations, according to a Goldman Sachs research, cross-country bond yield correlations could be driven by time-varying co-movement between both expected short-term rates and term premia.

It’s an understatement to say that the recent uncertainty about the Fed’s policy path may have caused the term premium to rise. With forward guidance anchoring short rate expectations, the significant influence of term premia in driving rates volatility seems to have increased. In sum, what appears to shape the yield curve today is a bit more nuanced than what the above theories may collectively help to explain.

The Fed’s Terms

Following the FOMC’s September meeting, Presidents Kashkari, Daly, Logan, Governor Waller and Vice Chair Jefferson remarked that the rise in the bond yields recently has the same tightening effect as a hike.

“In part, the upward movement in real yields may reflect investors’ assessment that the underlying momentum of the economy is stronger than previously recognised and, as a result, a restrictive stance of monetary policy may be needed for longer than previously thought in order to return inflation to 2 percent. But I am also mindful that increases in real yields can arise from changes in investors’ attitudes toward risk and uncertainty. Looking ahead, I will remain cognisant of the tightening in financial conditions through higher bond yields and will keep that in mind as I assess the future path of policy.” - Philip N. Jefferson, Vice Chair of the Fed

“If long-term interest rates remain elevated because of higher term premiums, there may be less need to raise the fed funds rate.” - Lorie Logan, President and CEO of the Dallas Fed

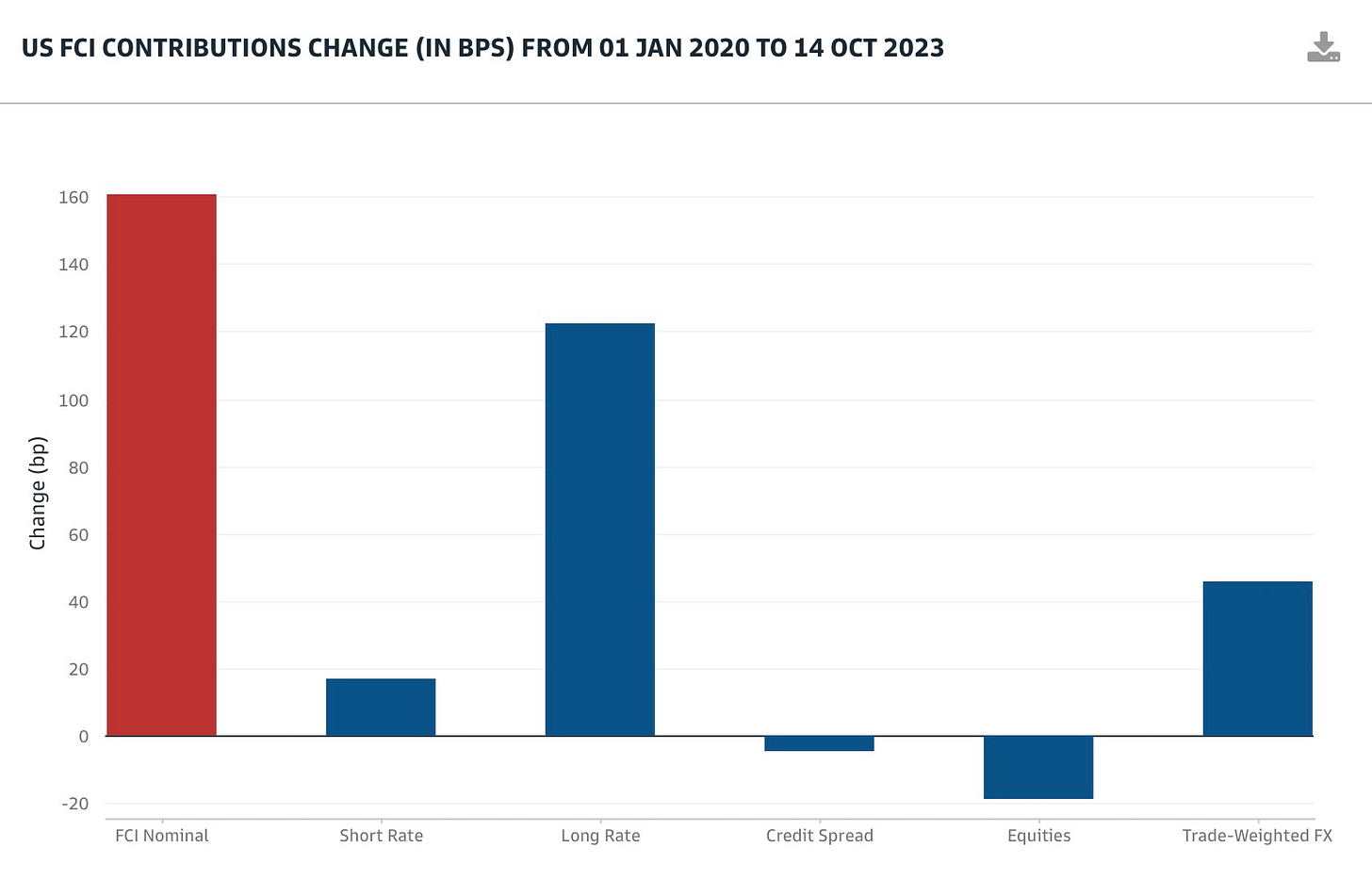

The tightening of financial conditions, which include the long and short rate, the equity and the credit market as well as the FX, is a measure of how well the Fed’s hiking efforts are working. Since 2020, the long rate has been the major contributor towards financial conditions tightening. Countering this effect of the tightening have so far come from the equity and credit market components. Having said that, the effectiveness of this passthrough of the long rate effect in terms of tightening onto the real economy is unknown.

Despite the recent behaviour of long-term interest rates, the Fed will need to remain vigilant and data dependent to really know whether hikes are still on the cards or whether higher rates for longer are required.