What is normal when you’re normalising

A brief run-through of the Fed balance sheet

On June 1st, 2022, quantitative tightening (QT) will start again, to be done at twice the pace and size of the prior QT cycle. QT affects the US economy by reducing the money supply. Currently, the Fed balance sheet is composed of many short duration instruments, and this means, merely letting it run off will also result in a much faster reduction.

If hiking and easing Fed fund rates are the main dish, then controlling the Fed balance sheet is the dessert, although I don’t think many would find either particularly appetising. This is reflected in the sequencing of policies where the Fed generally begins tightening financial conditions by hiking rates first, followed by tapering asset purchases and reducing the balance sheet, and if still required, the Fed would consider asset sales.

Balance sheet management has been an interesting monetary policy innovation. To further appreciate this, we could have a brief look at the balance sheet policy history over the past decade:

History of balance sheet policy

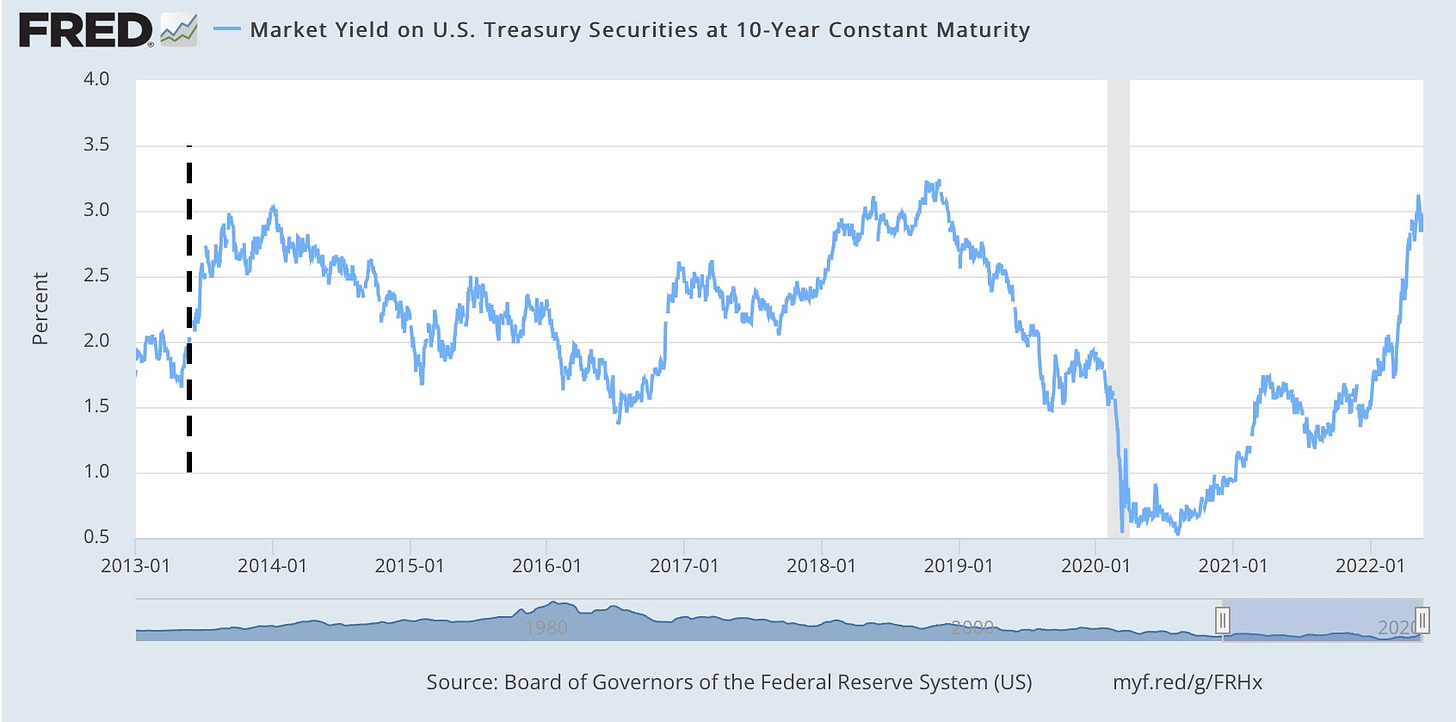

On 22nd May 2013, Chair Bernanke stated that the Fed would start tapering asset purchases at some future date, and good Lord, how the markets reacted! Photos of tapir, that black and white animal with the short, prehensile nose trunk circulated around Twitter. The negative shock from that announcement compelled many bond investors to sell. The yield on 10-year US Treasuries rose from 2% in May to 3% in December. This was henceforth called the ‘taper tantrum’.

At the end of 2017, having waited for two years since the first hike, the balance sheet runoff commenced after the Fed had raised the rates several times to reach around 1.25%. This runoff was done with a monthly cap of $10bn which steadily increased to a max of $50bn per month in 2018.

Before the last cycle, the Fed had not attempted to reduce the balance sheet. With no prior experience of where the level of balance sheet size can be safely reduced to, extreme caution was required. The idea was to maintain more than sufficient reserves while being mindful of the low interest rates environment at the current time. The Fed even repeatedly sent out surveys during the time to bank officers to ask them what their “lowest comfortable level of reserve balances” is.

The ratio of reserves to nominal GDP early 2019 was around 8% with no signs of financial distress from the markets. Come March 2019, the Fed reduced the speed of the runoff in case they had overshot the ‘safe’ level, and by October the same year, the Fed concluded that the runoff had indeed overshot. The Fed then had to resume asset purchases to restore the balance sheet to the appropriate level.

And then the pandemic happened. Support for the economy was needed and the FOMC stepped up its balance sheet expansion, taking on “broad and forceful measures to preserve the flow of credit in the economy.” Between March 11 and August 12, 2020, balance sheet size increased from $4.3 trillion to a peak of nearly $7.2 trillion in early June that year, decreasing a bit to under $7 trillion as of August 12.

In July 2021 as the pandemic looked to be more under control, the Fed had put out forward guidance that there will be a reduction in asset purchase towards the end of the year. There was fear of the repeat of the 2013 ‘taper tantrum’ but surprisingly, investors were rather relaxed hearing the announcement. The treasury yield stayed at 1.3% and didn’t even return to its previous peak just a few months before, in April. It could be that the guidance in 2021 was largely expected whereas the one in 2013 caught investors by surprise.

In that, there may be proof that changes, even big ones are ok if properly explained and announced far in advance. The window of the announcements probably can grow smaller and smaller as investors are more familiar with the normalisation process and assured that all the safeties are in place.

The balance sheet normalisation process

The balance sheet policy’s main transmission mechanisms are one, the signalling channel and two, the portfolio rebalancing channel, or more specifically, its sub-category, the duration extraction channel.

The signalling channel works via market expectations on the future short-term interest rate, e.g. an announcement of increases in balance sheet size can push up inflation expectations as it is interpreted as reinforcement of a continued accommodative stance.

Formally, the duration extraction channel is the interaction of size and duration as measured by the weighted average maturity balance sheet. The duration channel can come into effect when duration is taken out of the market by the Fed while its balance sheet size rises in tandem. Duration extraction can also work without altering the balance sheet size if the Fed sells short-term and buys long-term bonds.

In terms of size reduction, Goldman simulations found that a 25bp boost to 10y term premia from runoff affects financial conditions, growth and inflation as if there was a 25bp rate hike, The Chicago Fed President Charles Evans affirms this in a recent interview, but thinks the effect is closer to 50bp.

Studies show that for every 1% of GDP of asset purchases, the 10y Treasury yields is depressed by 4bp. However, the signalling channel only applies to expansions and not reductions of balance sheet size. When the balance sheet is reduced instead, the runoff effect increases 10y Treasury yields by only half the amount, i.e. 2bp per 1% of GDP.

This year marks the second cycle of the Fed balance sheet reduction. In general, how the Fed does this is by adjusting the amounts reinvested of principal payments received from securities held in the System Open Market Account (SOMA). Beginning next month, principal payments from securities held in the SOMA will only be reinvested to the extent that they exceed monthly caps.

Due to the pandemic stimulus, the balance sheet had increased to nearly $9 trillion today. That is a massive amount of liquidity to be reduced, so it helps that the cap is set much higher than before. The monthly cap would be set at $95 billion and is split $60bn-$35bn between Treasury and mortgage-backed securities. The caps would be set at half of those levels for the first three months of runoff.

The ratio of reserves to nominal GDP is now around 17%, higher than what it was in 2019. Even with the coming big reduction, the terminal level would still suit the Fed’s aim of ‘ample reserves regime’ as the Fed intends to slow, and then stop the decline in balance sheet size when reserves are somewhat above the level it judges to be consistent with ample reserves. Hopefully, there’s not much danger of liquidity stress this time as Fed intends to prudently pull up earlier rather than later, when there’s still room for error.

The term ‘ample reserves’ specifically refers to the minimum amount of reserves which enable the Fed to conduct policy without having to actively manage the supply of reserves. However, how this judgement of ‘ampleness’ is determined is not so clear, but it will probably involve monitoring banks’ liquidity stress, deposit growth, funding outflows and costs of funding.

Price signals from overnight interest rates in money markets could be a valuable guide this time. Regardless, what this ideal, equilibrium size of a central bank’s balance sheet liabilities may vary throughout time in response to various domestic and global conditions.

To see what happens when there is a mismatch of ‘availability’ to the immediacy of ‘need’ and the importance of backstops, let’s look back to what happened in 2019:

The safety mechanisms

For many years, the effective federal funds rate (EFFR) had been well-behaved, sitting within the specified range until 16th September 2019. So did the secured overnight financing rate (SOFR), which never moved beyond 20bp on a day. On that day and the following, overnight money market rates spiked, volatility went crazy and EFFR broke the ceiling of the FOMC target range. The extraordinary level and volatility of rates in secured and unsecured took everyone by surprise. Sharp rate movements in the repo market lead to pressures in the fed funds market.

The 16th saw SOFR printing at 2.43%, while the EFFR at 2.25%, 13bp and 11bp above the day before, respectively. The 17th saw SOFR greater than 5%, compared to EFFR at 2.3%, This prompted the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to announce its repo operations on the 17th to the tune of at least $75 billion daily. Reserves fell by $120 billion over two business days. On the 18th, the markets were calmer and the rates moved back closer to the average.

What could have led to this? Firstly, some depository institutions’ reserve holdings may have been at all time lows, frictions in the interbank market made the allocation of reserves across institution less than efficient. Thus, even though reserves were adequate in aggregate, individual sums demanded by each institution was not met due to this inefficient allocation.

Other reasons include some domestic dealers charging higher spreads to ultimate cash borrowers to make up for the intermediate costs they face, quarterly corporate tax payments that were due on September 16 were withdrawn from bank and money market mutual funds and the $54 billion long-term Treasury debt settled on September 16 increased the Treasury holdings of primary dealers that purchase these securities at auctions and finance them through the repo market.

Following that, in July 2021, the FOMC established a domestic standing repurchase agreement (repo) facility (SRF), which serves as a backstop in money markets. It works by reducing occasional pressures in overnight interest rates to push EFFR above the target range. This way, spillover from repo markets to the fed funds market is effectively limited.

There are other facilities on top of boosting the size and frequency of the traditional repos such as the Temporary FIMA Repo Facility, discount window credit, Primary Dealer Credit Facility, Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility and many more.

The Fed had said that the standing repo facility will function only as a safety mechanism, or backstop tool instead of de facto liquidity provision. There is an argument that it can also be used in conjunction with SOMA, therefore reducing the need for the SOMA portfolio to be as large. The counterpoint against the argument is that SRF counterparties might be tempted to take on more liquidity risk than would be prudent. On the other hand, SRF accepting only high quality liquid securities mitigates this problem somewhat.

To note, whereas the risks from portfolio rebalancing effect are concentrated at the beginning of the QT, the risks of funding markets stress are towards the end of QT, when liquidity levels are much lower. A thing to keep in mind when looking at various backstops or safety mechanisms is at what point in the timeline of the QT that they will be most needed.

Limits of balance sheet policy

In truth, the only reason to pay attention to balance sheet policy is if it’s not conducted properly, or there are not enough safety measures prepared, in which case we could run into liquidity stress. QT means banks need to be mindful of their the ability to sustain or grow deposit balances and watch out for the possibilities of higher costs of funding.

Nonetheless, possibilities of ‘taper tantrum’ and overshooting the equilibrium level means balance sheet policy must be carried out with greater care compared to rate hikes. In addition, it is good to ensure that the balance sheet reverts to an ‘ample’ and definitely not ‘overblown’ size as a matter of discipline.

Is tweaking the size of the balance sheet some magic elixir to controlling the financial conditions of an economy? As was said earlier, balance sheet policy in the US is only a sideshow, the funds rates are still the main mode of Fed monetary policy as the efficacy is better clearly seen and calibration of it is faster and easier.

So, what is normal when you’re normalising:

In a predictable and timely manner

Maintaining ‘ample reserves regime’

The rate of reduction can be less conservative when there are safety measures

The equilibrium size is linked to the growth of the economy

Being cautious of overshooting the equilibrium size

Shrinking the balance sheet when it is at its size today is a good thing

Longer term aim of shifting the composition to mainly Treasuries

The normalisation process could go on for a while (4-5 years)

I’ve been looking for some insight on The Fed Res’ QT program. Thank you Amni! You must have had a British Education as it’s evident from your use of (s)’s for (z)’s like we do in the States.

Thanks again.