The fascination with the ability of yield curves to predict recessions goes as far back as the late 80s, when Harvey (1988) began looking at yield curves to predict consumption growth. Fast forward to today, we are still ambivalent about the usefulness of the yield curve as predictor of recessions. Therefore, I thought, why not collect what we know about the inverted yield curve thus far? So, let’s try and read the tea leaves that is the inverted yield curve at the bottom of the market cup.

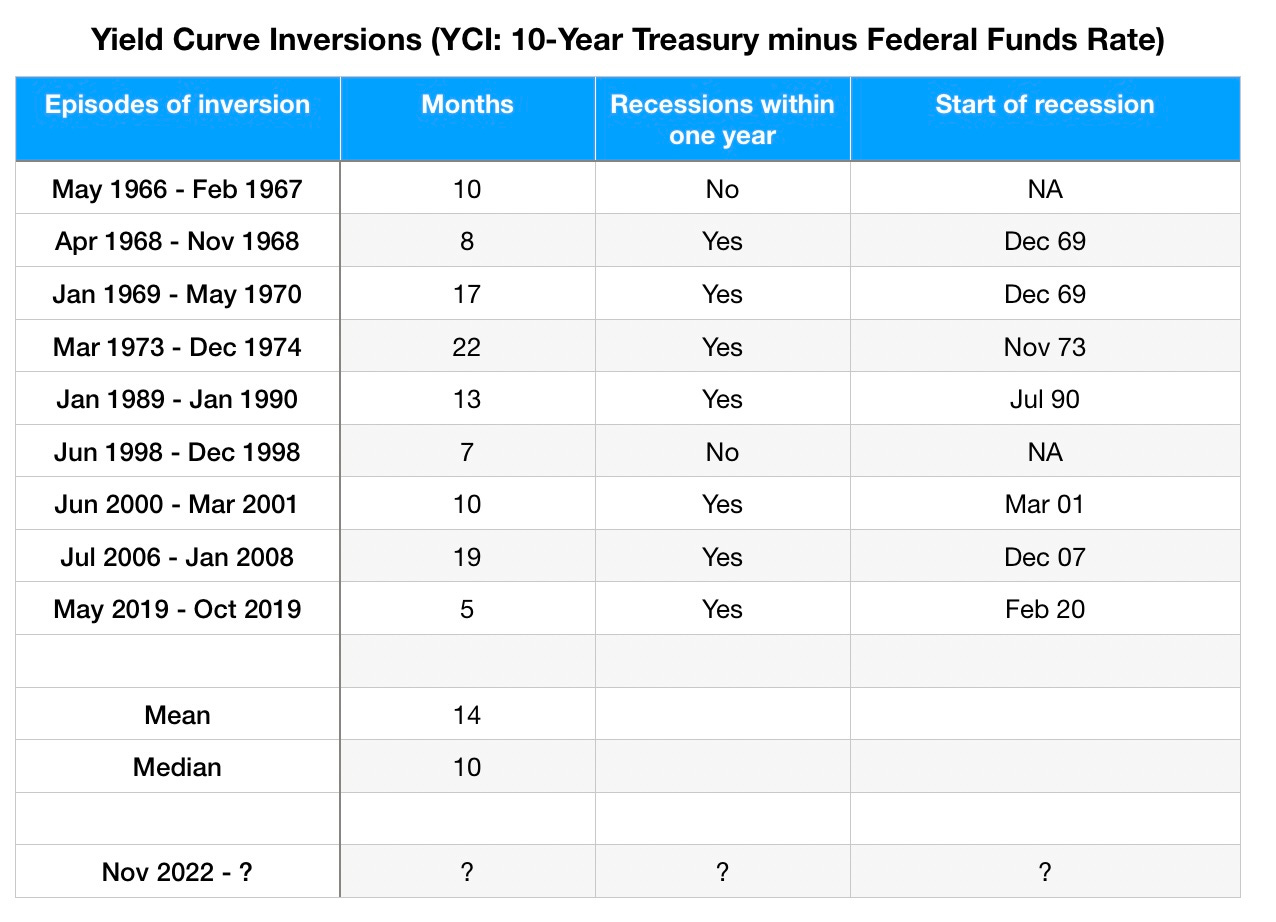

An inverted yield curve occurs when the yield gets lower as the maturity increases. Since the 1960s, yield curve inversion (YCI) normally precedes recessions. The exception to this rule occured between 1966-1967, where a recession was narrowly avoided and in 1998, where there was only a very small degree of inversion.

The propensity for recessions when tightening occurs is due to the increase in the fragility of the economy, which leads to a rise in unemployment. Unemployment rising more than 0.3% on a three-month moving average basis is sufficient condition for recessions to occur.

Which curves do we use?

The theory of yield curves employs many muses, or rather, many types and maturities, but which ones would give us better macro signals?

Engstrom and Sharpe (2019) argue that using short-term forward spread, i.e. the spread between 18-month and 3-month interest rates, best tracks near-term monetary policy expectations. We can also look at real (inflation-adjusted) spread measures. Logically, this should better reflect policy stance and expected growth. Practically however, this is sometimes not the case as the real spread may prove to be a poorer fit than nominal spread, reducing confidence in using the real spread for forecasts.

Alternatively, a commonly used interval is the 2s10s (i.e. the spread between the 10-year and 2-year Treasury rates), but questions arise whether this is the best predictor. The dominant challenge in using this curve is the term premium. Over the last fifty years or so, the term premium have been structurally depressed, and even more so for the past two decades. Due to this, there is a tendency for the 2s10s curve to over-predict the relationship between the curve and recessions. There are, of course, ways to get around this - by calibrating the models using past cycles data or taking into account the expectations component of the curve, as well as various other methods.

Regardless of the choice of rates, the spread is normally positive, i.e. long-term rates greater than short-term rates. The thinking is that when the spread declines, reaching negative, the probability of a recession rises.

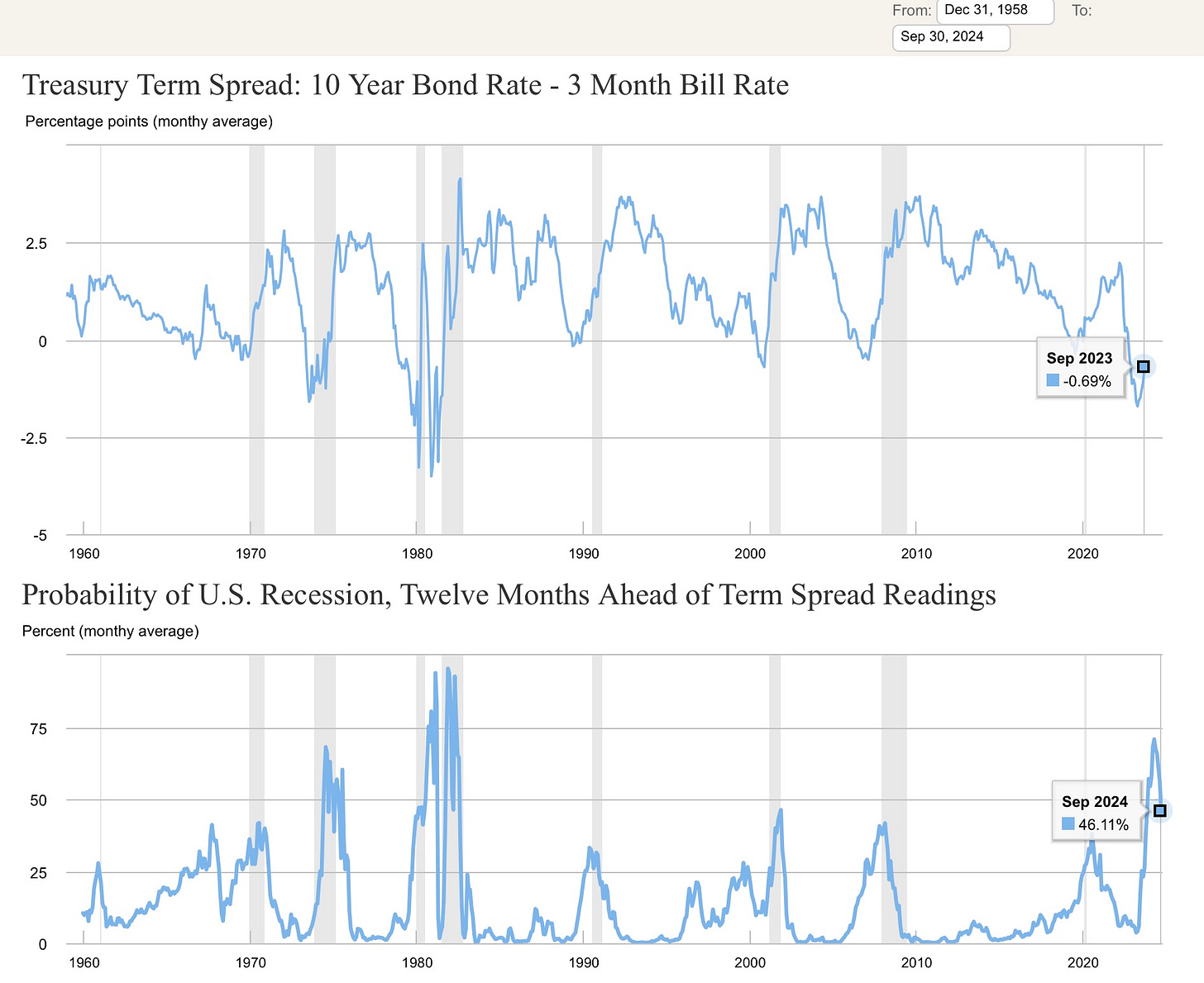

There is one tool that can quickly chart this, from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York website, which is the 10-year and 3-month Treasury rates spread. The chart is conveniently accompanied by another chart showing the probability of recession. According to the NY Fed, the nominal yield spread in September predicts a 46% probability of recession in 12 months.

Likelihood and duration of inversion

YCI is more likely to happen when the bond risk premium is low, hence, a slightly tighter monetary policy is enough to invert it. In addition, the length of time the yield curve remains inverted is also key. A short flip here and there and a well-behaved core inflation diminishes the significance of the inversion.

How long can a YCI last? A YCI is always transitory but inversions can last longer when core inflation is higher.

(The years 1979-1982 are omitted from the table below as the FOMC were employing a different policy regime targeting narrow money growth which makes interest rates and the yield curve more volatile and therefore, not comparable. The regime produced deeper YCI pre-recessions. A shallower steepening compared to more recent events followed after the inversion.)

Fundamental driver of YCI

In 2018, Powell put forward inflation as a function of inflation persistence and labour market slack. To combat inflation persistence (i.e. a state of high inflation that remains despite resolution of supply issues and excess demand), the Fed would have to set the terminal rate to be higher than the neutral rate for a period of time until the target of 2% is achieved. This restrictive policy will undoubtedly increase the chances of a recession. Hence, fundamentally, the Fed’s tendency to hike when inflation is high can lead to YCI.

As an aside, just like there is no long-run effect on output stemming from demand shocks, output is also not contemporaneously affected by monetary policy shocks. Moreover, even though only future output is predicted by the yield curve, the short rate also factors into the prediction. The yield curve’s predictive ability depends on the market reactions to monetary policy. Hence, should the monetary policy regime and market response change, so would the yield curve’s predictive ability change in tandem.

Technical drivers of YCI

The yield curve can be decomposed into the expectations component and the term premium component. Overall, the yield curve has been flatter compared to previous cycles because of the lower 30y yields. This is because the term premium has been compressed at longer maturity (see “Terms of Endearment”).

The compression may also stem from long run real rate levels that are low. The idea of secular stagnation, or low r*, still permeate investors’ thinking. However, the recent experience of the economy’s resilience despite the Fed’s hikes may lead investors to revise their estimates of r* higher. This revision in turn, could moderate future YCIs such that they are less severely inverted and display more ‘normal’ levels.

To note, the expectations component can better show the market’s expectations for the Fed’s hike path as the term premium component might be affected by demand and supply factors. Therefore, a flat term premium component is not a good recession predictor whereas a flat expectations component could perform better as predictor. Lange (2018) slightly differs, finding not only that the term premium is important for predicting GDP but also that expectations are better for predicting recessions.

Now, let’s look at the shape of these things.

The slope of YCI

If the market believes that there is a high probability that the Fed will ease, then we could see a significant inversion at the front end. The reasons the market may think that the Fed will ease include: first, the expectations of a recession and hence the Fed will need to ease later to support the weakening economy or second, the expectations of a ‘soft landing’ and hence afterwards, the Fed will need to ease to reach their target of 2% inflation.

If the expectation is a recession, the market will expect lower long run rates, but, an expectation of a ‘soft landing’ may lead the market to be more optimistic and price in higher long run rates relative to the other scenario of recession. However, the range between these two scenarios is not very big. In fact, the distribution of views about the short rate is wider than this range. It seems that the market has more confidence in their views of the long rates than the closer in time short rates. That reduced confidence at the short end relative to long also means that “bad news is good news” such as negative labour market data reduces the current inversion.

A significant inversion can be moderated if the Fed eases aggressively or the long run real rates eventually rise or a combination of both. However, the likelihood of the Fed easing aggressively is low as the Fed would have to consider risk management of the easing path. To add, it is not only the Fed’s interest rate policy but its balance sheet policy such as quantitative tightening which also affect the yield curve. The central bank’s asset holdings tend to reduce the slope of the yield curve.

Bulls and bears, steep and flat

YCI may be a snapshot of the yield curve in time but have you considered the dynamic movements of the yield curve from normal to flat to inverted and back again in reverse? Perhaps we should be acquainted with the terminologies, so I will insert them here, because, why not.

A steepening yield curve is when the spread between short term and long term yields widens. A flattening yield curve, the opposite.

A bull-steepener is when the short-term interest rates fall more quickly than the long-term interest rates. The steepener happens when the market is expecting a recession, in which case the Fed would be required to cut rates. In the short run, these cuts would be good for stocks (hence, bullish).

A bull-flattener, where the long-term interest rates fall faster than the short-term interest rates, tends to be seen late-cycle, leading to flight-to-safety trades and a fall in inflation expectations. This change usually anticipates the Fed reducing short-term rates, which is good for stocks (hence, bullish).

A bear-flattener, where short-term interest rates rise faster than long-term interest rates, typically overlaps with mid-cycle periods, when a strengthening recovery leads the market to price in more policy tightening, and risk assets such as equities and credit see negative returns (hence, bearish).

A bear-steepener is when long-term interest rates rise faster than short-term interest rates. The steepener happens when the market witnesses economic resilience and therefore expects the Fed to have to keep the rates “higher for longer”. Keeping rates high for long is bad for stocks (hence, bearish).

Cases of bear steepening of 2s10s Treasury yield curve when it is inverted is rare. The years in which bear steepening occured in the US are 2010, 2013, 2015, 2016, 2021, and 2023, if you include the one this summer.

In July 2023, 2s10s curve demonstrated the deepest inversion for 40 years at 110 bps. From very inverted levels, the 2s10s US Treasury curve steepened, most of it driven by a rise in the longer-term interest rates. This move reflected the improvements in ISM and GDP growth expectations.

Apart from growth expectations, bear steepening can alternatively stem from rising real rates or term premium, especially at later stages of the steepening. YCI may un-invert (i.e. back to flat, then, to positive) through the Fed easing and/or the repricing of long run real rates and term premia.

YCI, then and now

Perhaps the predictive ability of YCI was better pre-2000s, when the levels were more closely related to inflation and GDP, and consequently, monetary policy. Today, investors demand much less inflation premium. In addition, the distortions stemming from flight-to-quality demand for Treasuries, demand from pension funds and of course, the Fed’s QE have lowered the 10- and 30-year yields. This means, for the YCI to significantly indicate recession, the levels would have to fall far below 0 bp, e.g. below -50 bps for a 2s10s curve.

The yield curve today has been in the state of inversion since November last year, albeit it seems that the level is heading towards 0 bp. At the end of October, yields at the long end fell faster than at the short end, with 2s10s falling lower from -16 to -27 bps.

Fed’s actions and the YCI

If core inflation is close to the target, then the Fed will be more careful in tightening to avoid a hard landing. This will ensure that an already inverted curve will not steepen further as a result of the Fed’s policy, although it could still invert more due to other factors.

Having said that, an unintentional hard landing may still happen. If the economy is slowed to below trend, it would take very little reversal of the currently tight labour market to have the combination of a fall in income and spending, as well as rising unemployment, for these factors to reinforce each other, propelling us towards a recession.

What are the factors that may persuade the Fed to hike? First, if the economy stays strongly above its potential while the labour market remains tight. Second, if core inflation is drifting higher. Third, if time and time again, when the FOMC stops tightening, the market takes this as a green light to rally which causes an easing of financial conditions. This waters down the tightening effect of monetary policy.

Financial conditions usually ease towards the end of a hiking cycle and this easing begins well ahead of the Fed reducing short-term rates. This anticipatory move may give the Fed the incentive to hike just a tad more to ensure that the policy does not lose traction. Powell recently opined that the increase in the long rates had helped tighten financial conditions. This tightening was then promptly reversed by the market’s exuberance. Perhaps Powell would have been wise to not imply that the long rates had “done the job”.

Lastly, if it’s a close call between hiking and pausing, the costs and benefits of making an error in tightening/not-tightening are asymmetrical. If the Fed ends up tightening too little and fails to tame the inflation, the credibility of the central bank could come into serious question. If the Fed ends up tightening too much, this can be reversed, but with the Fed’s credibility still intact-ish. This asymmetry means that there may be a bias for the Fed to over-tighten.

Reading YCI tea leaves in context

Those who have considered the YCI as a signal for recession have sometimes come away a little confused, akin to a man taking a brisk walk and upon finding a hole in the ground, exclaims, “It is my experience that when I find a hole such as this it should soon be filled with water”, and when the hole remains empty is then sorely puzzled why that is so.

What then, should we advise him? It would be good to tell that man to lift his sight off the ground and see whether the sky is clear or filled with dark clouds before assuming there would be a puddle, i.e. the presence of the hole merely increases the possibility of a puddle forming. Analogously, YCI describes the hole (recession conditions) that the puddle (recession) can form in. Perhaps YCI becomes a more reliable recession predictor when interpreted within the context of monetary policy events and expected economic growth, including other factors and events that affect inflation expectations and term premium.